How to avoid dividend disaster

Thinking about common reasons a company might stop paying a dividend can help income investors avoid disappointment.

Mentioned: Endeavour Group Ltd (EDV), Endeavour Group Ltd (EDVGF), Bayer AG (BAYER), Amazon.com Inc (AMZN), BHP Group Ltd (BHP), Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA), National Australia Bank Ltd (NAB), Netflix Inc (NFLX), Philip Morris International Inc (PM), Rio Tinto Ltd (RIO), Vornado Realty Trust (VNO), Wesfarmers Ltd (WES), WiseTech Global Ltd (WTC), Xero Ltd (XRO)

Buying high quality dividend shares can be a great way to grow an extra source of income. And if history is a guide, dividends are likely to make up a big chunk of the total return delivered by equities. My intention today is to help you avoid buying stocks that suddenly pull the rug on their dividend.

Before we start, it’s important to note that Australians are more used to fluctuating dividends than investors from other countries. This is because over half of the ASX’s companies are in cyclical sectors like mining and energy, where dividends are often based on a pre-agreed percentage of earnings. As these earnings can vary a lot, payouts rarely grow in a straight line like they are expected to in the US.

What we are trying to avoid here are huge dividend disappointments. The kind that completely remove income you were counting on and make your purchase price look far less attractive. We’re going to use the inversion method made famous by the late Charlie Munger. We are going to consider the main reasons a company might slash their dividend and look to avoid them.

“All I want to know is where I’m going to die, so I never go there”-- Charlie Munger

Why do companies stop paying dividends?

Earnings fall due to a cyclical downturn

Cyclical companies often have very attractive dividend yields at the peak of their cycle, when recent earnings and dividends look strongest. But if the cycle turns and earnings fall, there will not be enough profits to pay the same level of dividends as before. Mining is a classic example here.

In 2015, BHP (ASX:BHP) paid a dividend of $1.40 per share. This was the final year where results were boosted by the “China boom” in metals. For 2016, BHP’s dividend was just $0.29 per share and did not surpass $1.40 until 2022. If you are considering a cyclical company for its dividend, you should be wary of the cycle turning and look at the long-term track record. How did dividends change in previous down-cycles?

The company has borrowed too much

If a company carries a lot of debt, interest payments can eat up a large percentage of its profits. If these earnings fall for any reason, or the debt is refinanced in a period of higher interest rates, the company may not be able to cover both its interest expense and the dividend. And let’s not forget about the principle that needs to be repaid. If there’s a downturn or earnings fall due to cyclicality or intense competition, the burden can start to look overwhelming. You can read my thoughts on how to assess a company's debt load here.

The company faces short-term uncertainty

Many companies saw their earnings visibility fall to zero during the pandemic. This was an extreme scenario but industries often go through periods of high uncertainty. If this happens, management will often cancel or cut the dividend to conserve cash and cover fixed costs until normality resumes.

Covid aside, a recent example – also linked to balance sheet strength – was the New York City based Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) Vornado Realty Trust (NYS:VNO), which suspended its dividend in April 2023. They did this because bank failures in the US led to concerns that commercial real estate firms might find it harder to refinance their debt. I owned the shares then and still do today.

The company suddenly faces big cash outflows

A company might also cut its dividend because of a sudden increase in costs. A good example here are companies that incur big legal damages. In February 2024, Bayer (BUD:BAYER) reduced its dividend to the lowest amount allowed by German regulators. This was partly due to the company being ordered to pay $2.25 billion USD in damages to a single person after its Roundup weedkiller product was linked to cancer.

Earnings have fallen for other reasons

Business cycles aren’t the only reason that earnings fall. Sometimes it’s just good old capitalism. If a company doesn’t have a moat, it’s likely that competition will erode their returns on capital over time. And if a company is disrupted completely – like what Netflix (NAS:NFLX) did to Blockbuster – the death of its business usually involves the death of its dividend some time before.

A company’s industry could also be in secular decline. This hasn’t been too much of a problem for tobacco companies like Philip Morris (NYS:PM), which have been able to offset falling volumes with price increases and new nicotine products. But not every company can do this. For companies like this, you’re likely to see the company pay out an increasing percentage of their earnings out as dividends because they can’t reinvest them in the business profitably. This could boost dividends in the short-term but eventually the well will dry up.

Flipping the script

By now we’ve established some common reasons a company may cut its dividend. By flipping these on their head, we arrive at a “wishlist’ of things likely to protect a dividend.

Other things to consider

You may have noticed that I’ve avoided backward looking metrics so far. This is because they can be dangerous when used in isolation. Consider a company’s dividend yield. This is widely used as a guide for what income, in percentage terms, investors may expect each year. But it is usually calculated by dividing last year’s dividend by today’s share price. As a result, it ignores the chance that future dividends will be different.

In saying that, backward looking metrics can still be useful. This is especially true for the dividend payout ratio, which I alluded to earlier.

The dividend payout ratio

A company’s dividend payout ratio shows you what percentage of earnings were paid out as dividends over the past twelve months. A lower dividend payout ratio means the company has more room to maintain the latest dividend if earnings fall. But that doesn’t automatically mean a lower payout ratio is better.

If a company has plenty of profitable ways to invest in future growth, they should probably pay out a lower percentage of their earnings in cash. If a company operates in a more mature industry and has fewer opportunities like this, they should probably return more of their profits to shareholders.

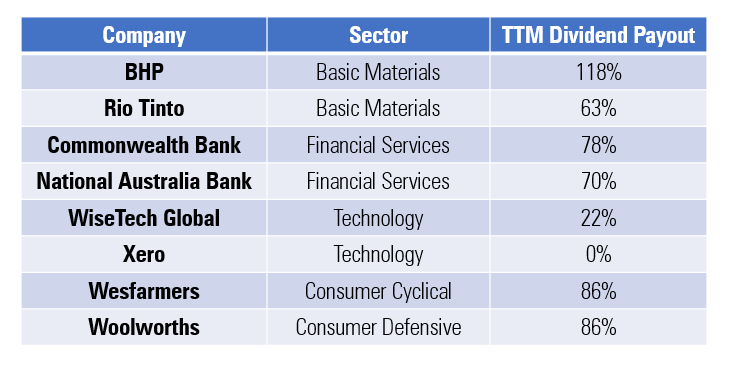

I’ve shown the trailing twelve month dividend payout ratios for some of the biggest stocks in the ASX below. You can see a clear difference between leaders in mature industries (like big four banks) and companies in higher growth sectors like software.

When you are looking at a company’s payout ratio, you want to think about whether it is suitable for the company’s maturity and if it is sustainable.

If a company’s payout ratio is over 100%, you would want to understand why this happened. They may have used cash that was lying around to pay a special dividend to shareholders. Perhaps they distributed funds from a one-time gain like a demerger. Or maybe they wanted to avoid a big dividend cut, so used cash to plug an earnings shortfall.

Either way, it’s unlikely that a company could pay out more than 100% of its earnings forever. Sometimes a payout ratio is enforced on a company. For example, REITs are legally obliged to pay out 90% of their profits as dividends and often get close to the 100% mark.

An example

So far, we’ve looked at some classic setups to be wary of. We’ve also looked at how metrics like the dividend payout ratio can give you further insight. I’m now going to apply these to ASX stock Endeavour Group (ASX:EDV).

Endeavour operates Australia’s largest network of brick-and-mortar liquor stores, with more than 1,600 outlets across the well-known Dan Murphy's and BWS brands. Endeavour also has substantial interests in hotels and electronic gaming machines, with over 12,000 gaming machines across its portfolio of more than 300 hotels, pubs, and clubs.

Cyclical or fairly predictable?

Over three quarters of Endeavour’s earnings come from liquor retailing. As alcohol is a consumer staple, our analysts think that Endeavour’s sales should be fairly resilient to economic downturns. This, and the maturity of the alcholol business in Australia, is reflected by our analysts assigning Endeavour a low Uncertainty rating. Buying in at a cyclical peak looks like less of a concern here.

Too much debt?

Endeavour earns more than 8 times its annual interest expense and has leverage of around 3x. This means that around three quarters of Endeavour’s assets are funded by debt. For a business that has a Wide Moat and should be resilient to economic downturns, this seems sustainable. Our analysts view Endeavour’s Balance Sheet as being “fairly strong".

Competitive threats?

Our analysts have assigned Endeavour a Wide Moat rating due to scale and cost advantages in its liquor retail business. A Wide Moat rating means that our analysts think that Endeavour’s competitive advantages will persist for at least 20 years.

Amazon (NAS:AMZN) has been touted as a long-term threat, but our analysts think this is immaterial for now. Most alcohol is consumed within 24 hours of purchase, which makes waiting for an online delivery unattractive relative to shopping in person or using “Click and Collect” services like those offered by Endeavour’s brands. Amazon has also failed to meaningfully scale up sales of alcohol in other geographies so far.

Big potential liabilities?

Endeavour does not mention any major outstanding legal cases in its Annual Report. Its main industries alcohol and gaming do introduce a level of regulatory risk. However, this is more likely to surface in the form of tighter regulation than legal action. Our analysts feel that Endeavour’s regulatory risks are softened somewhat by the amount of tax paid in both its alchohol and gaming segments, which are an important source of government funds.

Endeavour’s payout ratio

As Australia’s dominant liquor retailer, Endeavour holds a leading position in a mature industry. It isn’t surprising, then, that it paid out around 75% of its 2023 earnings in fully franked dividends. A 75% payout ratio doesn’t leave a huge amount of room for error, but there is some breathing space and Endeavour is unlikely to see big swings in earnings.

As the payout ratio is already quite high, any potential dividend growth would presumably come from increased profits. Our analysts think that Endeavour’s group revenue and profits will grow by around 3% per year over the next decade, roughly in line with the expected growth of Australia’s broader liquor retailing market.

Something to keep in mind

These checks can help you avoid common dividend pitfalls. But if there’s one guarantee in life, it’s that the future is unpredictable. Your best defence against dividend disappointment is always likely to be earnings growth and a durable competitive advantage.