Corporate Australia is still a man’s world, but it’s improving: Gender diversity in focus

Whilst Australia has achieved a lot, equality in the corporate context has not yet occurred. However, it is encouraging that it remains a high priority for our biggest companies.

Emma Rapaport, editorial manager, Morningstar contributed to this article.

Today is International Women’s Day, a day where we celebrate the social, economic, cultural, and political achievements of women. It’s a time to reflect on how far we have come, but also how far we still have to go.

Let’s look at this through the lens of Australian corporations and consider diversity and inclusion purely from a female gender perspective. We’ll first demonstrate the gender gap in corporate Australia and why equality is important, before exploring how the financial services industry is working to close the gap and where further improvements can be made. Finally, we’ll discuss something individual investors can do to support a more equitable future.

Exploring the gender gap

Gender equality is one of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which have been designed to create a framework to help guide the development of a sustainable future. Many Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) listed companies are providing detailed reporting that links their business activities to SDGs as sustainable investing becomes increasingly important to attract capital and remain competitive. A recent joint study between RMIT and CPA Australia found one of the top 3 prioritised SDGs by ASX 150 companies in 2019 and 2020 was SDG number 5, gender equality.

Source: United Nations

Whilst Australia has achieved a lot, including electing many more women to company boards, equality in the corporate context has not yet occurred. However, it is encouraging that it remains a high priority for our biggest companies.

The below chart lists the top 10 ASX listed companies by market capitalisation and outlines their own company score cards for gender diversity across female executives and directors. Woolworths leads the pack with 60 percent female representation across executives and directors; NAB, Westpac and Wesfarmers all tied with 33.33 percent female representation in their senior leadership teams.

Source: Morningstar Direct

Australia’s workplace gender equality agency report, Higher Education Enrolments and Graduate Labour Market Statistics 2021, shows that more women are graduating from higher education than men. Yet, from the moment they are employed, women are typically earning less. Compound this over many years of employment it puts women at a distinct financial disadvantage. The report says, “the data confirms stark graduate and postgraduate gender pay gaps across the majority of study fields and industries in Australia.” The gender pay gap has yet to be rectified. This is not equitable. From there the disadvantage continues, women as a cohort are not securing as many leadership positions, there are fewer female executives, CEOs, and board members.

Because the issue is multi-faceted, it is difficult to unpack the data to point to exactly why this is occurring. It’s likely a combination of things:

- Unconscious bias

- Women tend to take up more of the unpaid household duties

- Women are caregivers to children and elderly parents

- A lack of affordable childcare meaning women have career gaps to take care of children

- The need for more flexible work arrangements to fit in around family responsibilities

- Women being paid less than their male counterparts leading to disengagement or resignation

Regardless of the reasons, women are trailing behind in the corporate ranks or worse, they drop out of the workforce altogether, meaning the pipeline of senior women to take up executive roles, leadership and board positions is thin.

Why gender equality is important

Good governance and the bottom line

Diversity is an important component for good governance as different perspectives and insights are expected to improve outcomes. Management consulting firm McKinsey has been a leader in the field reviewing gender diversity and its impacts for over 10 years, mostly in a US context. Their research has found a link between profitability and gender diversity. In 2019 they found top quartile companies for gender diverse executive teams were 25 percent more likely to have above average profitability than companies in the fourth quartile.

While McKinsey research points to quantifiable positive outcomes, it is difficult to corroborate this with data in Australia as gender diversity at the board level is still in a transitory phase in Australia. Furthermore, anecdotally women locally tend to be appointed to smaller companies with more challenging track records, so performance data is skewed against them.

To add further complexity, academic research that highlights that if women with similar backgrounds to male board members are appointed, the benefits of diversity to overall company performance are questionable. Are you getting diversification of thought or just gender?

The best people for the job

Discrimination, purposeful or not, is never OK. There is a school of thought that the board selection process is biased towards males. Whilst it may not be deliberate rather an unconscious bias it is still an issue that needs attention. We tend to like and be more comfortable around people like us and this can cloud our decision making. If the selection process is mired in bias, then the candidate pool will be more concentrated than it should be leaving a smaller selection of like-minded people with similar experiences, meaning the best person for the job may not be secured.

Sheryl Sandberg believes this to be so important that she has founded a gender equality not for profit called LeanIn and has built a program to address unconscious bias in the workplace. Unconscious bias happens to be the theme for International Women’s Development Day 2022.

Making progress through funds management

Sustainable investing

In funds management, there is increasing demand for Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) investing evidenced by the flow of money into sustainable or ESG strategies as investors seek to align their investments with their personal values. This includes incorporating assessments of companies’ gender diversity to determine how they might respond to ESG risk. Why gender diversity? The reasons vary from better governance to better investor outcomes, supporting corporate strategy and performance. It’s also the right thing to do, forming a fairer and more equitable society.

This agenda has been driven by shareholder activism, the 30% club, women on boards, male champions of change and likely others drawing attention to this issue requesting companies both report and explain female representation or lack thereof.

Last year, for the first time a major milestone was achieved. Every ASX 200 listed company reported at least one female on their board. This result is even more impressive when you consider it was done without legislated quotas.

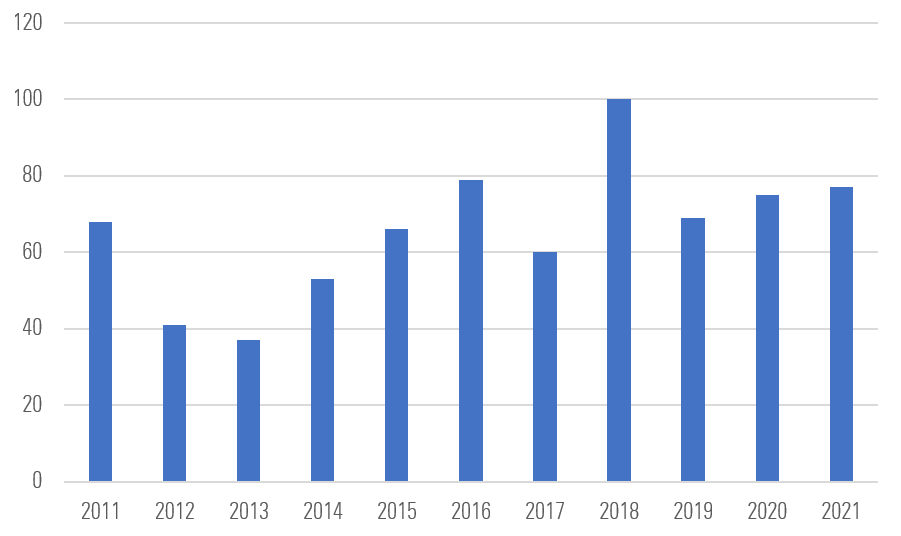

The below graph shows the number of female board appointments over a 10-year period.

Number of women appointed to ASX 200 boards

Source: Australian Institute of Company Directors as of 30 November 2021

Given gender equality is a top priority for our largest listed companies there must be concerns that should they not appropriately address this issue they may have capital flows impacted. Institutional investors have been actively engaging on this issue for many years. Companies that are not taking this serious risk divestment and/or being left behind.

The visualsation below demonstrates the impact of gender in the ASX 300. The more a name is represented the larger it is. Male names in teal, female names in purple. Michaels, Andrews, and Marks do well in the executive ranks and Davids, Peters, and John’s in the non-executive. It’s striking how few purple names there are in the executive ranks.

Source: Ownership Matters

Room for improvement

Golden skirts

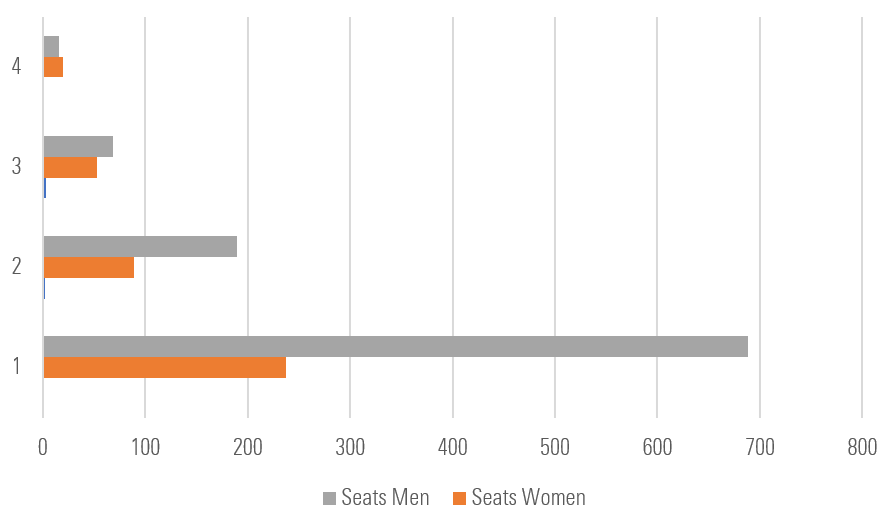

Data shows us that board concentration is an issue. Once a first board seat is secured odds are high that a second or more will be forthcoming.

Ironically as more women make it onto boards a similar pattern emerges. A chosen few women become appointed to multiple boards. There is even a term for it “golden skirts “and it’s not just a local phenomenon, it’s globally applicable. As of October 2020, in a 3-year period 40% of all serving women directors accepted an additional appointment compared to 17.5% of all men.

Number of board seats ASX 300: Women and men

Source: Ownership Matters

Meritocracy fallacy

Often, we are told executive and board positions should be based on merit. This sounds reasonable in theory but when the odds are stacked against women the moment they enter the workforce, it would seem meritocracy is not yet feasible. Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor Emilio J. Castilla uncovered the paradox of meritocracy; people can show greater levels of gender bias when they are operating in a context that emphasises meritocracy.

If the corporate environment does not provide a level playing field for women, then what can be done?

Don’t mention quotas

Quotas are one way to overcome gendered issues. Quotas sets clear and measurable targets; they can also affect change in a timelier manner than other options, but they can also cause divide. There has been success offshore when board appointments are mandated by law via quotas, but the risk is that person’s appointment is undermined, considered less worthy than had the quota not been in place. Tokenism. This is a conundrum.

The other option which is the path corporate Australia has taken is through other measures such as ‘leave it to the market to decide’. This has caused a rise in shareholder activism on certain topics of interest. Over a protracted period, institutional shareholders have pushed companies on female representation and their results have helped to increase the number of senior female appointments over time. It’s been a slower process but a successful one.

The below graph captures the trajectory of the change.

Source: Ownership Matters

As an individual, what can you do?

You can follow in the footsteps of the institutions and lend your voice to this issue. You can ask companies about their board composition, their board selection process and whether they strategically review gender pay gaps within their firm. Australian shareholders have had a significant impact already as owners of the companies and can continue to do so at an individual level.

Talk to your fund manager about how they are interacting with boards and understand their policy for investing in companies that do not have adequate female representation at the executive levels. Ask the fund managers about female representation withing their own company. Do they have any female portfolio managers, board members or executives? Asking questions is important way to communicate key issues.