How MeToo forced companies to see the business risks of sexual misconduct

Change is slow but inevitable.

In the five years since a wave of sexual harassment and abuse claims reignited the #MeToo Movement and electrified a national conversation about harassment in the workplace, companies still struggle with these incidents, highlighting the serious business risk of sexual misconduct.

Sexual harassment has always been a problem in the workplace, but it burst into public view in October 2017 with several news reports that dozens of women had accused movie producer Harvey Weinstein of rape, sexual harassment, and abuse over 30 years. Weinstein was fired by the company he founded, later charged, tried, and in 2020 sentenced to 23 years in prison.

Weinstein’s arrest galvanised the #MeToo Movement, originally started by New York activist Tarana Burke in 2006, prompting women to share their own experiences with rape and sexual abuse. Some broke nondisclosure agreements, or NDAs, to do so.

The fallout was immediate as #MeToo revelations hit corporate America.

- News surfaced in late October 2017 that Fidelity Investments dismissed two portfolio managers after they were accused of inappropriate behavior. The firm has no tolerance for harassment, CEO Abby Johnson told her employees in a video message.

- Guess GES stock plunged in February 2018 after reports that co-founder Paul Marciano was accused of sexually harassing employees.

- In January 2018, Wynn Resorts WYNN shares collapsed after a Wall Street Journal report detailed harassment and assault accusations against founder and CEO Steve Wynn.

- At Alphabet GOOG, some 20,000 Google employees in 50 cities walked out in 2018 in a protest against sexual harassment, demanding that the company end forced arbitration, publicly release a report on sexual assault at the company, and introduce a process for reporting sexual misconduct.

To be sure, sexual harassment is a persistent problem. Yet the outlook for a safe and inclusive workplace is steadily improving. For instance, the US Congress recently passed a bill that would bar the use of forced arbitration to settle sexual assault and harassment claims in the workplace, a tactic critics say shields perpetrators.

And increasingly, companies are expanding the number of female leaders, adding protections for women, and adopting specific policies around gender equality. The table below shows the companies that Equileap, which researches gender equality, believes are leaders in this area, including advertising giant WPP (WPP) in the United Kingdom and General Motors (GM) in the United States.

Shareholders have played an important role, too, pushing companies to adopt women-friendly policies.

The cost of misconduct

As evidence emerged that harassment hurt productivity, profitability, and stock prices, companies took notice.

Firms with extreme levels of sexual harassment, as measured by an analysis of online job reviews, regularly exhibited a drop in productivity and performance reflected in profitability, labor costs, and stock prices, according to a study led by Shiu-Yik Au, an assistant professor of accounting and finance at the University of Manitoba.

Indeed, firms in the top 2% of sexual harassment complaints saw declines of 4% on return on assets, 11% in return on equity, and an increase of 7% in labor costs during a five-year period around the year that sexual harassment became an issue in online job reviews. In addition, the stock fell by a risk-weighted 13%.

“These results indicate that sexual harassment has a highly detrimental effect on firm value, and employee voluntary reporting can be a valid disclosure mechanism when firms are disincentivized to reveal bad news,” according to the report.

Focus shifts to female leadership, policy changes

Companies moved to strengthen employee protections, updating policies related to sexual misconduct.

Boards began to offer employment contracts that gave them greater discretion to dismiss executives for sexual harassment, discrimination, and other violations of company policies. Authors led by Rachel Arnow-Richman of the University of Florida Levin College of Law documented a rise in such #MeToo termination rights, “bringing contract terms more in line with changing expectations” and produced “greater institutional accountability for sex-based misconduct.”

Firms also took steps to bolster female leadership and increase the number of women in management. California passed a law requiring two women on every board for companies headquartered in the state. Greater diversity would curb groupthink, the theory went, and putting women in charge would change corporate culture and attract younger employees.

“If you ask millennials what’s important to them, [female leadership] is a big piece, much bigger than it was for boomers,” said Julie Gorte, executive vice president at Pax World Funds. “Parity in the boardroom and C-suite helps. With more women in positions of power, it becomes a signal that the woman you harass today could be your boss tomorrow.”

Today, sexual harassment is seen “as a civil rights violation that needs wide attention,” said Dieter Waizenegger, executive director of SOC Investment Group, which leads corporate governance initiatives on behalf of US union pension funds.

“The cultural norms have changed dramatically, as victims started to speak out, name names and put themselves in jeopardy,” he said. “There’s more accountability for the perpetrators particularly if they’re in top management positions. We want to make sure this transparency continues.”

Shareholders join the fight

Much is owed to the shareholders who pushed companies to change with the growing movement toward stakeholder capitalism, which believes equal consideration to employees, suppliers, customers, communities, and shareholders is critical to a company’s long-term future.

Shareholders mounted campaigns for wage parity and transparency about corporate wage policies. Other investors encouraged companies to perform equal-pay audits of workforces and disclose how they would achieve their commitments to improve conditions.

For example, Arjuna Capital, a prominent impact investor, pressed Microsoft (MSFT) and a series of Fortune 500 companies to detail their sexual harassment policies and how they monitor them. Arjuna also pushed companies to address gender pay-equity and reporting transparency.

Boards also began tying executive compensation to environmental, social, and governance factors, including how companies treat employees.

And since knowing the problem is critical to solving it, investors began prodding companies to detail the demographic data on gender, race, and ethnicity by job category that they disclose to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in EEO-1 reports.

State Street (STT), which has nearly $4 trillion under management, recently said it will vote against directors of S&P 500 companies that don’t disclose EEO-1 reports. According to nonprofit researcher Just Capital, some 55% of Russell 1000 companies now disclose racial and ethnic data. In 2021, 94% of IBM (IBM) shareholders approved a proposal for the company to report diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts.

“MeToo, combined with George Floyd and the pandemic and disparity between the haves and have-nots were a perfect storm,” said Haleh Modasser, author of Women on Top and a financial adviser at Stearns Financial in Chapel Hill, NC. Indeed, Modasser credits these issues for “mounting inflows” into the sustainable portfolios in her practice.

A persistent problem

After The Wall Street Journal reported in November 2021 that Activision Blizzard (ATVI) CEO Bobby Kotick had covered up claims of sexual harassment and rape at his company, investors called for him to be removed. The stock took a beating--which in turn made the company a ripe acquisition target for Microsoft. Morningstar senior analyst Neil Macker does not expect Kotick to remain in his position for more than a few months after the deal is completed sometime in 2023. Today, federal and state regulators are investigating how Activision handled the claims of misconduct.

Microsoft is reviewing its own sexual harassment and gender discrimination policies after reports that founder Bill Gates sought inappropriate relationships with employees. Nearly 80% of shareholders voted recently for a review of Microsoft’s policies to protect workers against abuse and unwanted sexual advances.

McDonald's (MCD) has been the subject of numerous harassment lawsuits and EEOC complaints. In September 2021, the EEOC sued AMTCR, which operated more than 20 McDonald’s restaurants in Nevada, Arizona, and California, and accused the franchise owner of allowing “workers to be subjected to egregious sexual harassment.”

A month later, McDonald's workers walked out at restaurants in 12 U.S. cities in protest. Separately, McDonald’s fired its CEO, Steve Easterbrook, in 2019 after learning he had an inappropriate relationship with an employee, as companies in the wake of #MeToo became more sensitive to power imbalances and potential harassment.

In 2020, 51% of companies globally still hadn’t published an anti-sexual-harassment policy, according to the 2021 Gender Equality Global Report and Ranking published by Equileap. Spain was the leader in this effort, with 73% of companies having an anti-sexual-harassment policy, followed by France, Italy, and Canada. The laggards included Hong Kong, Singapore, Sweden, the UK, and Australia.

“The fact that only five out of 10 companies globally are publishing sexual harassment policies means that there is significantly more that could be done to explicitly condemn sexual harassment and gender-based violence by over half the companies researched, that between them employ 98 million people,” said Diana van Maasdijk, CEO of Equileap.

The way forward

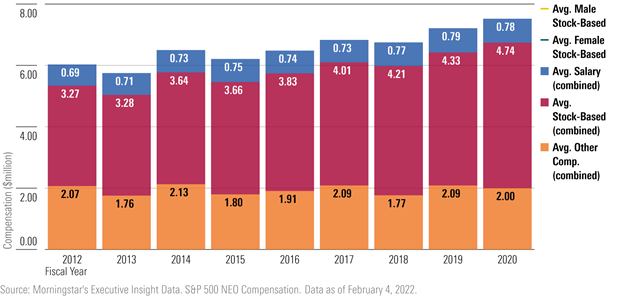

The problems haven’t been easy to fix. According to Morningstar research, pay for women in the C-suite at the largest US companies was 75 cents for every dollar earned by men at the top of the corporate ladder in 2020, down from 85 cents in 2018 and a record low for the nine-year period since 2012.

For women, a widening pay gap

Part of the difference in pay has to do with the increase in equity-based compensation for executives, most of whom are men.

Meanwhile, women are making only incremental progress into the C-suite: Only 16% of named executive officer positions at S&P 500 companies were held by women in 2020, up from 9% in 2012.

“They’ll have to wait until 2060 to reach parity at the present rate of progress,” said Jackie Cook, stewardship director at Sustainalytics, a Morningstar company.

The number of female executive officers inches higher

Further down the ladder, women have been 1.8 times more vulnerable than men to the financial fallouts of coronavirus, according to research by McKinsey. Women accounted for 54% of job losses in the U.S., despite making up just 38% of the labor force.

One place where headway is being made: A reversal of the damaging practice of NDAs, that in the past prevented victims from coming forward. Late last year, California passed the Silenced No More Act, which will make it easier for employees to speak out about racism, sexual harassment, and other workplace abuses without being stifled by NDAs. The new law also expands a ban on confidentiality and non-disparagement clauses.

As the annual meeting and proxy season gets started, shareholders will continue to be hard at work. On March 4, Apple (AAPL) faces shareholder proposals to address persistent gender and racial pay inequity, to perform a third-party audit to analyze and improve the company’s civil rights impact, and to report on potential risks to the company related to its use of NDAs and other concealment clauses.

Later this year, look for Tesla (TSLA), which last year was ordered by a federal jury in California to pay $136.9 million to an employee who said he was the victim of racist abuse at Tesla's Fremont plant between 2015 and 2016. California also sued the electric car maker for alleged racial discrimination and harassment, following claims from workers that they were the targets of discrimination, including the use of racial slurs by co-workers. Last year, Nia Impact Capital proposed that Tesla report on its use of mandatory arbitration, in which employees must submit to arbitration rather than bring their claims to court. Nia made its proposal last year and it garnered 46.4% support at Tesla’s annual meeting.

Another proposal passed that asked Tesla to provide more data about its diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts, arguing that increased diversity at Tesla will help ensure that it remains competitive and innovative.

This year, thanks to the federal legislation on forced arbitration, Nia plans to rewrite its proposal to focus on racial harassment.

“We’re going to stay in there until we get this done,” says Kristin Hull, CEO of Nia.