Australian income investors shouldn't fear higher interest rates: Morningstar Special Report

Morningstar's cost of equity already incorporates higher interest rates.

This is a snippet from Morningstar's Special Income Report: 10 franked income-stock ideas for Australian investors. Morningstar Premium subscribers can view the full report here.

Australian income investors have been impacted by falling interest rates in recent years, which has crushed interest rates on deposit accounts and compressed yields on residential real estate. However, with most Western central bank interest rates close to zero, it's understandable that investors seeking income are concerned about interest rates and income stock yields moving higher, potentially causing capital losses from income stocks.

Morningstar's fair value estimates are based on our assessment of a "fair" return for equity investments which we consider to be 9% per year for an "average" stock, roughly equal to the long-term historical total return of the equity market. Put another way, we believe equity investors should require a return that is equal to a "midcycle" risk-free interest rate of 4.5% plus an equity risk premium of 4.5%. Although our risk-free rate assumption may seem conservative relative to the current risk-free rate, it provides a margin of safety against the risk of interest rates moving higher.

Interest rates have fallen in recent decades

Source: Reserve Bank of Australia, Morningstar

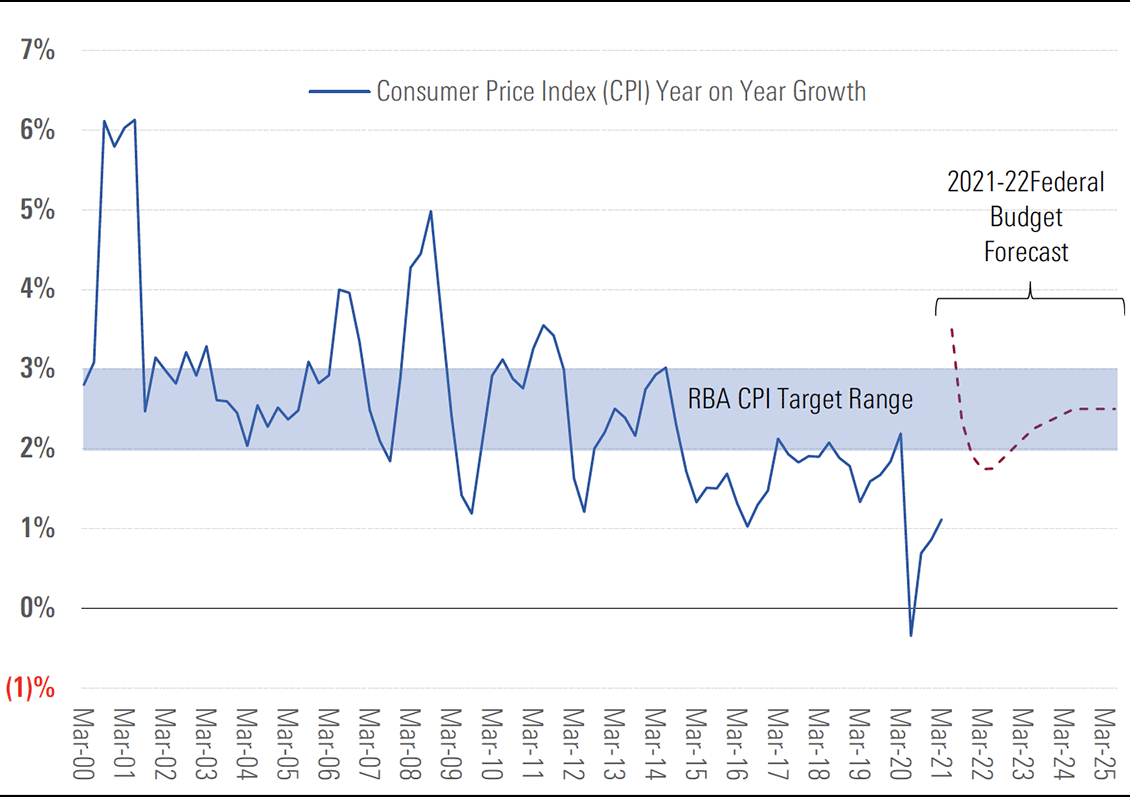

Inflation could push rates and yields higher but possibly not to long-term historical levels

While we can see rising inflation risks and the likelihood of interest rates increasing over time, it will be a long road for rates to get back to historical long-term averages, if they do. While we do see some risk to equity valuations from rising interest rates, we do not think those risks are acute or are likely to suddenly materialise, nor should they deter investors from equity investments. The latter is supported by the relatively low returns on offer in alternative investments such as fixed interest.

The Covid-19 pandemic caused the Reserve Bank of Australia, or RBA, to cut its target cash rate to practically zero to stimulate the economy, but low interest rates aren't a uniquely virus-related phenomenon. Rather, both nominal and real interest rates were already at record lows before the pandemic and have arguably been trending lower for the past 40 years. Economic analysis published by the Bank of England in 2020 also indicates that real interest rates have been gradually falling for centuries rather than decades, implying that weak interest rates could be at least partly a structural rather than cyclical phenomenon.

In 2017, the RBA published a report entitled, The Neutral Interest Rate, which found that the "neutral" interest rate, which enables full employment and stable inflation, had fallen to around 1.0% in 2017 from 2.5% in 2007. This implied a "neutral" nominal cash rate of around 3.5%, assuming 2.5% inflation. However, in June 2021, economists at the Commonwealth Bank estimated the RBA's nominal cash rate would be "neutral" at just 1.25%.

In July 2021, the governor of the RBA, Philip Lowe, also said that Australian "full employment" likely corresponded to an unemployment rate in the low-4% range and that low wage growth would likely prevent the RBA's cash rate from increasing before 2024.

It's worth remembering the RBA's mandate is to "…contribute to the stability of the currency and full employment..." which it achieves by "…conducting monetary policy to meet an agreed medium-term inflation target…" Importantly, the RBA is not tasked with managing residential real estate prices, meaning management of inflation, particularly wage inflation, and unemployment will remain primary objectives of the RBA. However, inflation has consistently plotted below the RBA's target range of 2% to 3% over the past decade, and wage inflation has missed the 3% target, with the RBA's forecasts for wage growth repeatedly too optimistic over the past decade.

Inflation has missed the RBA's target in recent years

Source: Reserve Bank of Australia, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Morningstar

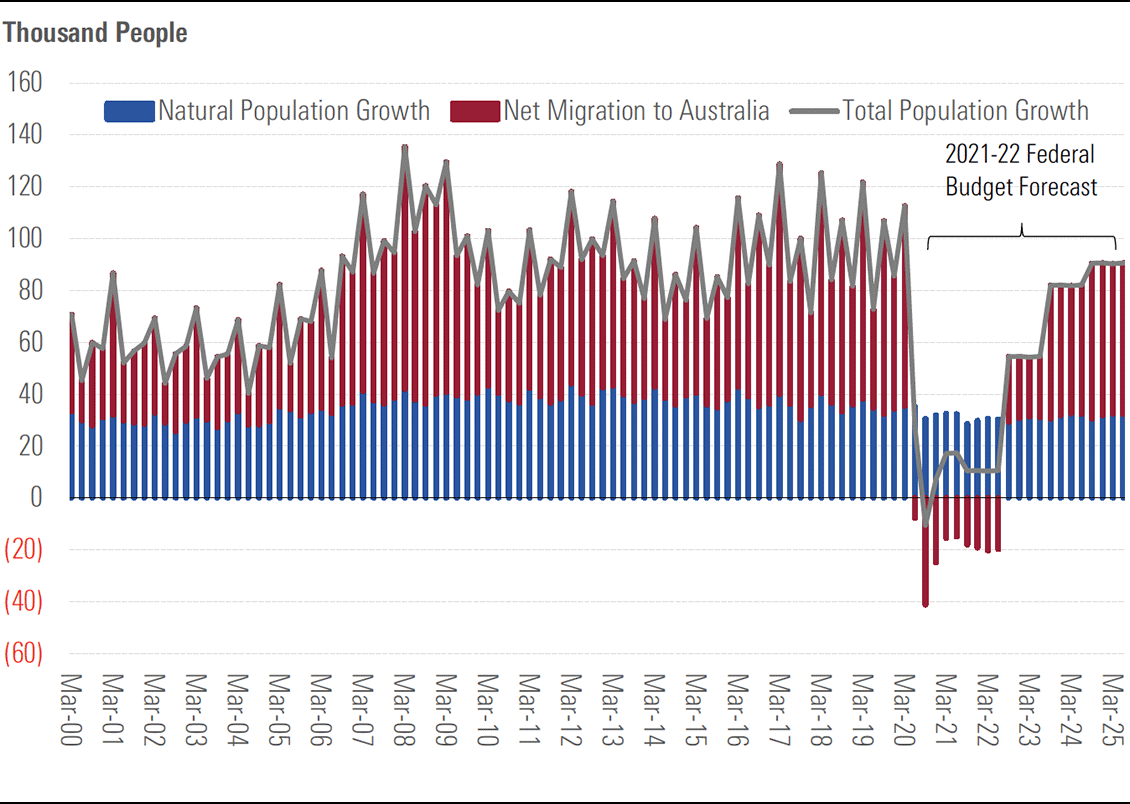

In May 2021, the Australian federal government released its 2021–22 federal budget and highlighted the speed with which gross domestic product, or GDP, and unemployment had recovered. Although the current increase in virus cases and related lockdowns, particularly in Sydney, mean the short-term economic outlook has since deteriorated, it's likely the subsequent recovery will be equally quick as it was in 2020.

However, the bigger issue facing the RBA is what comes after the pandemic. For example, Australian GDP growth is particularly dependent upon Australia's relatively high population growth grate which in turn is based on relatively high immigration. Although unemployment has recovered quickly, international borders remain closed, and immigration has effectively stopped. RBA governor Philip Lowe recently indicated Australia's high rates of immigration are a headwind for wage growth, which leaves the economy in a catch 22 situation whereby immigration is needed for GDP growth but may stymie wage inflation, and therefore result in low interest rates, as occurred in recent years. The other challenge facing the economy is the increase in government and household debt which arguably creates a headwind to higher interest rates.

Immigration should recover from mid-2022

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian federal Government, Morningstar