Insurers need insurance too

Floods are a reminder of how insurers deal with natural catastrophes

After the flood came the bill. For Joe Wilkinson, the $13,000 price tag for flood insurance was too steep. He wasn’t alone. According to the ABC, which interviewed others like him, many found the price of insurance too high.

It’s an issue normally associated with individual homeowners, but the expense of insuring against natural disasters can also be a problem for insurers.

Natural catastrophes are unpredictable and expensive. To cope, insurers do what you do—get insurance. The industry calls it “reinsurance.” By sharing the risk, insurance companies spread the cost of catastrophe claims.

That helped Australia’s two largest insurers, IAG (ASX: IAG) and SunCorp (ASX: SUN), walk away from the March floods with only “a minor dent,” according to Morningstar equity analyst Nathan Zaia. Despite estimated claim costs of about $450 million between them, both insurers have yet to use up all their loss allowances.

“The floods will be a minor dent on earnings, but its small impact on one year’s profit, not an ongoing change in earnings outlook,” Zaia says.

“Before the floods, the insurers were a bit under their allowances. The floods have put them equal to or a little over their allowances. By no means have they blown out their allowances so far.”

Zaia’s fair value estimates for both IAG and Suncorp remain unchanged at $6.00 and $12.50 respectively. Suncorp closed Thursday at $10.32, a 17 per cent discount on fair value. IAG closed at $4.93, an 18 per cent discount.

The March floods are the latest in a string of natural disasters stretching back to the 2019-2020 bushfires. By last September, claims from the four most recent natural catastrophes had already totalled more than $5.2 billion. IAG has a market cap of $12 billion.

Catastrophes, insurance, and reinsurance

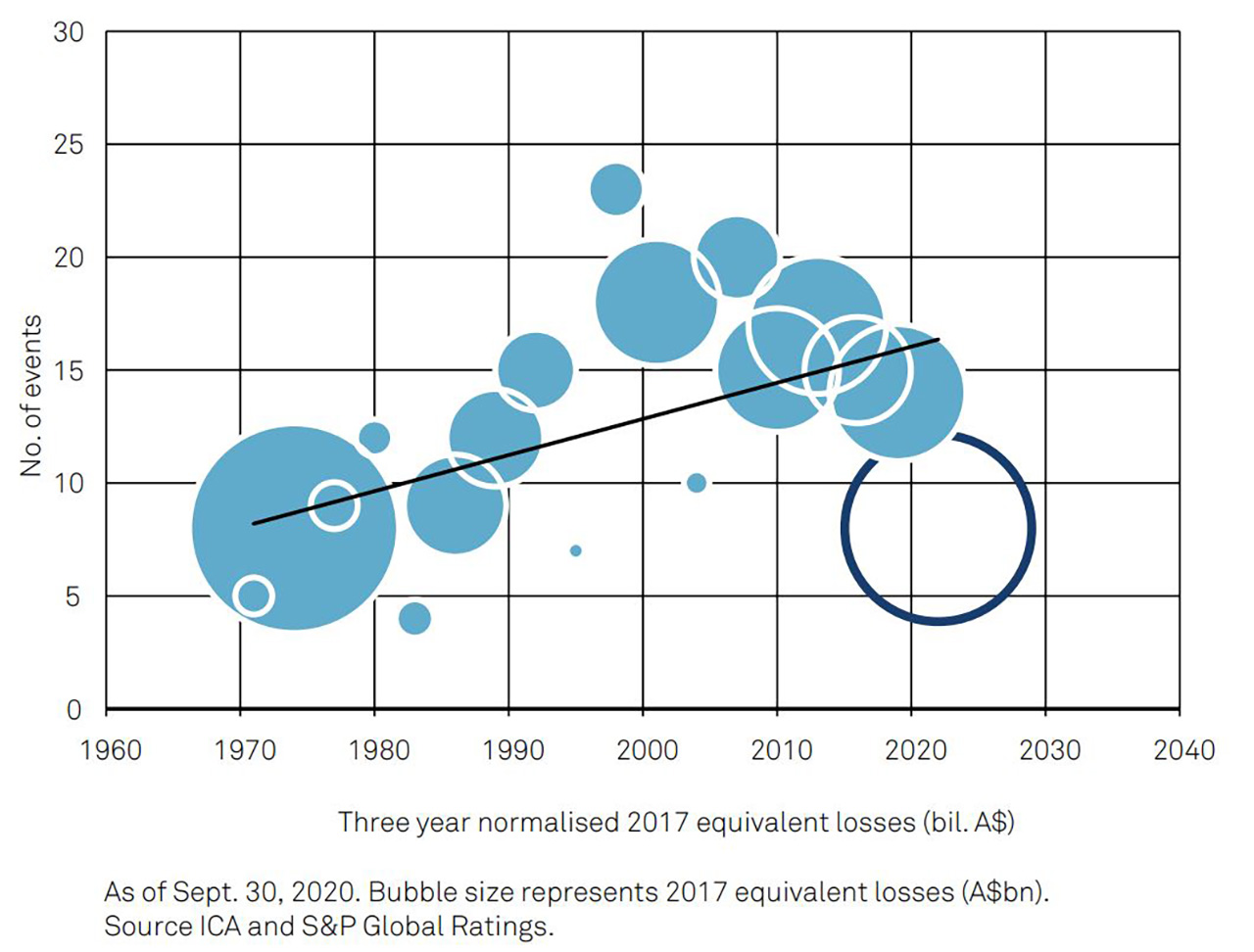

Declared catastrophes have been on the rise in Australia for 50 years. The usual approach to more risk is higher premiums and more reinsurance.

Declared catastrophes in Australia over time. Bubble size represents losses.

Source: 'Global Reinsurance highlights 2020,' by S&P Global Ratings. Page 44. Copyright © 2020 by Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC.

“Insurance premiums would have to go up if insurers were facing greater costs per year,” Zaia says. While reinsurance can cover many things, it’s generally for those larger natural hazard events.”

But a September 2020 report by S&P Global argued reinsurance was not enough. Over 2018 and 2019, reserves set aside for catastrophes at the three largest reinsurance companies fell by 40 per cent.

Rising prices and stricter conditions for reinsurance meant that other options are needed to insure against floods, fires, and earthquakes. The report suggested government-backed schemes or new capital from other investors.

Australian insurers are already some of the largest purchasers of reinsurance coverage in the world, led by IAG.

According to a 2020 report by McKinsey, a consultancy, more frequent catastrophic events could undermine insurer business models, by making some insurance too expensive for customers and impractical for insurers.

“The common catastrophe models, which are mostly based on historical data, are unlikely to accurately project risk because the climate now behaves differently,” McKinsey says.

Still, even with the jury out on whether climate change is driving more frequent extreme weather, catastrophe claims can still rise because of more construction in risky areas.

“I’m hesitant to definitively say weather events are so much worse,” says Zaia, “Take the recent rain. It’s not necessarily that we’re getting more rainfall, but that we’ve built in flood-prone areas where we previously wouldn’t have.

“Areas like Windsor and Richmond, in Sydney’s west, are on floodplains. The more we do that, the more damage we will get when we have these events.”

Because predicting the future is impossible, it’s ultimately a question of how much risk an insurer is willing to take. Investors should keep the same in mind.

“It’s a reminder for investors that there will be unpredictable expenses,” says Zaia.

“Reinsurance helps, but earnings can be volatile. I wouldn’t hold insurers as a steady dividend stream because there are periods where profits get wiped out.”