The three elements of a successful transition to retirement

Transitioning to retirement can be a perilous time for investors. A plan helps and here is mine.

Mentioned: Vanguard Australian Government Bond ETF (VGB)

My first job after university did not involve a lot of work. I worked for a bank in their fund administration arm and on an average day my assigned tasks took perhaps two hours. It was the days before flexible work and smart phones so I would sit at the office trying to get through each day until I could go home.

I was bored and had no interest in advancing in my present role. To say I wasn’t engaged is an understatement. Despite what many of my colleagues think I did not start working in the stone age. Which meant I had the internet. And as a 22-year-old who hated work I did what I thought was logical. I created a plan to retire early.

My original plan has evolved and I am no longer focused on an early retirement. Yet the plan remains in place. I even had a chance to test it when I helped my mother transition to retirement.

A couple caveats about my plan. My plan is based on how I am comfortable investing and my own life circumstances. Yours will different. My plan generally wouldn’t work for someone who does not have a self-managed super fund (“SMSF”). I will explain why.

There are three elements needed in a plan for transitioning to retirement:

- The withdrawal rate that will be used: This is how much of my portfolio I will spend each year. And yes for retirement accounts like super the government mandates withdrawal percentages. That doesn’t mean the money needs to be spent and it can be saved and invested outside of super.

- The approach to converting assets into cash flow: We spend our lives accumulating assets and need to convert those assets into cash to support day-to-day expenses. That can be done by selling holdings or by generating income.

- Asset allocation and the approach for dealing with a market plunge during the retirement transition: The sequence of returns matters when withdrawing money from a portfolio and not just the average return over a specific period. This is called sequencing risk and retirees who experience large drops in their portfolio early in retirement will run out of money faster.

My high level plan

I will use a two-bucket portfolio of dividend paying shares and cash as a basis for my retirement. Four years prior to when I plan to retire I will turn-off the dividend reinvestment in my portfolio and keep new retirement contributions in cash until I have five years of living expenses in cash.

In retirement the income earned in my portfolio and opportunistic share sales will replenish the cash bucket as I spend it down. My retirement asset allocation will be approximately 80% equities and 20% cash.

There are some terms in there that may be unfamiliar to some readers. I will explain them below. More importantly I will explain the rationale for the approach I plan to take. Maybe you will agree and maybe you won’t. At the very least it will expose some of the challenges during a transition to retirement.

The twin risks to retirement portfolios

Investing theory tells us that as we approach a goal like retirement it is important shift our portfolio into more defensive assets to limit volatility. It is more important to understand why than follow a rule of thumb.

This is to combat sequencing risk, which is a fancy way of saying that if the market drops significantly as you start drawing down your portfolio it may not last long enough to cover your retirement.

Many investors are confused about sequencing risk and an example is illustrative. We can use two scenarios to illustrate the risk. In both scenarios an investor has a $500,000 portfolio and withdraws $20k a year for 20 years to support retirement spending. The portfolio is 100% in the S&P 500.

Scenario A: An investor earns the actual returns on the S&P 500 from January 1st, 2000, for 20 years. At the end of the 20-year period the investor is left with ~ $165,000.

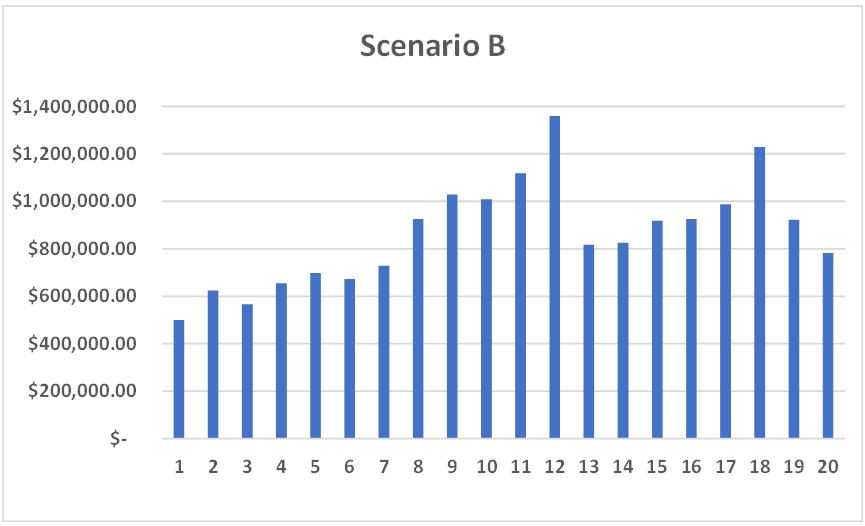

Scenario B: The same 20-year actual returns for the S&P 500 are reversed in order. In this scenario the actual return during 2019 occurs in the first year of this hypothetical retirement. The actual return from 2000 occurs in the last year of the 20-year period. You get the point. At the end of the 20-year period the investor is left with ~$782,000.

In both these scenarios the average annual return is the same. All I did was reverse the order. The outcomes are very different. I did pick a very specific timeframe since the decade starting in the year 2000 faced both the .com bubble bursting and the global financial crisis. The S&P 500 had a negative total return over that decade.

Sequencing risk is a legitimate concern. But longevity risk is also a concern which refers to outliving your money.

To address longevity risk the best approach is to keep growth assets in your portfolio. If the ways to address those twin risks seem conflicting it is because they are. The heart of this conflict is that none of us know how long we will live which makes it very difficult to plan retirement.

Aggressively de-risking your portfolio by shifting to defensive assets increases the chance you will outlive your retirement savings. Being too aggressive means that if the market drops significantly early in retirement you may never recover.

The bucket method of asset allocation

The bucket approach to portfolio construction is designed to mitigate the twin risks retirees face.

Sequencing risk exists because the spending needs during retirement necessitates the selling of assets in down markets. Forced to sell low there is less of an opportunity to take advantage of market recoveries. This means that a retiree could run out of money prior to death.

The central issue is not the market drop. That periodically happens in markets. The real issue is the need to sell during these downturns. The bucket approach addresses this issue by creating short, medium and long-term grouping of assets.

The short-term bucket is invested in cash and is designed to meet near term spending needs. If the market drops significantly retirees can draw on this cash instead of selling depressed assets.

The medium-term bucket is made up of bonds which have lower long-term expected returns but less volatility than shares.

The longer-term bucket addresses longevity risk by investing in shares.

Market conditions dictate when assets in the medium-term and long-term buckets are sold to replenish the short-term bucket.

Why a 4% withdrawal rate?

There are several intricacies involved with setting a withdrawal rate. My colleague Shani does a great job in this article explaining how the rule works.

The truth is that I don’t know my withdrawal rate yet. I am 45 and have a good deal of time prior to retirement. During that time my financial position will change, advances in healthcare will impact life expectancy and my priorities will change.

These unknowns are not a good reason to stick your head in the sand. I’ve assumed a 4% withdrawal rate because you can’t come up with a saving and investing plan without a withdrawal rate. I’ve estimated my retirement spending needs in a process I outlined in a 4-step process to figuring out retirement needs. I fully expect that plan to change.

I will reassess my withdrawal rate as I approach retirement. I’ve used conservative returns on my retirement portfolio to get to my target savings. If returns exceed those expectations I may use a higher withdrawal rate. As you age market returns play a bigger outcome than savings goals. That is just math. The larger the portfolio the less savings matter and the more returns influence how much money you have.

Why does my plan include five years’ worth of spending of cash?

The short answer is because I’m conservative. Under most scenarios holding this much cash will not maximise my wealth. And as investors we tend to think this is the purpose of investing and any investment strategy. I disagree.

The reason I invest is to meet my goals. In other words, it is to enable the life I want to live. And I haven’t taken a vow of poverty. I want a bigger portfolio because I want to spend more money. I also don’t want to spend my life worrying my finances. Missing out on the potential upside to sleep at night is a trade-off I’m willing to make.

Taken to the extreme this ‘sleep at night’ maxim can be a problem. Many investors are far too conservative to achieve their goals. But I’ve diligently saved for retirement from the start of my career, I have a retirement goal and I’m comfortable I will achieve it if I can manage to stay employed.

Any investor following a bucket approach will have to decide how much cash is right for them within the holistic goal of living the life they want. This includes spending needs and sleeping at night. A bit of market history provides some inputs into the decision-making process.

Since 1957 there have been 12 bear markets when the S&P 500 has dropped 20%. Australian markets largely correlate with US markets. In this case I’m fudging the numbers a bit and including a drop of 19.90% in 1990. The following chart shows the length of bear markets as measured by a fall of 20% from peak to trough and the length of time until a new bull market which represents a 20% rise from the low.

As we can see there were only two instances where the combined length of the bear market and a new bull market exceeded the 60 months of cash in my plan. Those are the .com crash of 2000 to 2002 and the global financial crisis of 2007 to 2009.

There are two caveats that are important. A portfolio that falls 20% and then recovers 20% doesn’t mean you have the same amount of money as when you started. You have less. That is illustrative of why selling at the bottom to pay for retirement expenses is such a problem.

The other caveat is that real life is not as clear as it appears in the rearview mirror of history. No investor would know they are in a bear market until the market passes the 20% threshold. I could still sell to replenish my cash bucket early in the slide after the peak. I wouldn’t have to wait until shares cross the technical definition of the bull market at a 20% recovery to start selling again. I’m trying to avoid selling in the depths of the bear market and before a meaningful recovery takes shape.

Why only two buckets?

Most bucket portfolios have three buckets. One for growth assets like shares, one for defensive assets like bonds and one for cash. I am one bucket short.

There are two reasons for this. The first is that I don’t like bonds. To me they aren’t worth it. This statement will probably get me kicked out of the simplistic school of asset allocation. But hear me out. According to Vanguard, over the last 30 years Australian bonds have delivered real (inflation adjusted) returns of 2.8% annually. Real returns on cash have been 1.5% over the same period.

Yes 2.6% is more than 1.5% and over long periods of times that difference matters. But at what cost? What they don’t tell you in the simplistic school of asset allocation is that bonds are volatile. Not as volatile as shares but significantly more volatile than cash which has zero volatility.

Contrary to the teaching at the simplistic school of asset allocation bonds often don’t move in the opposite direction of shares. The latest example was the bear market of 2022. Bonds can also meaningfully drop in price. Over the past 5 years the Vanguard Australian Government Bond ETF (ASX: VGB) has fallen 11.30%.

That trade-off doesn’t seem worth it to me. I don’t want to exchange a relatively small difference in real returns for volatility as I transition into retirement. I want my defensive assets to be 100% defensive which allows me to allocate more to growth assets. I believe given the high difference in the returns between growth assets like shares and bonds will mean a higher return for my portfolio over the long-term. And people can be retired for a long-time.

Do I have a different view of bonds now since I have a long-time frame until retirement? No. I still don’t want them. In this case I don’t care about volatility and want the higher long-term returns from shares. The same Vanguard data shows that Australian shares delivered 6.5% annual real returns over the last 30 years.

The second reason I’m comfortable without a bond bucket is because of the type of share investor I am. My portfolio is filled with large companies in non-cyclical industries that pay dividends. I focus on quality shares. That may mean I’m giving up some returns in bull markets. But I gain some protection in bear markets. That typically means my portfolio will be less volatile than the market. And with that we have solved the mystery of the missing bucket.

Why a SMSF?

The bucket approach requires customised asset allocation and the ability to pick the specific assets that are sold to support portfolio withdrawals. An SMSF provides this flexibility.

Different industry and retail super providers are offering varying degrees of customisation for members transitioning to retirement so my blanket statement that you need a SMSF may need to be amended under certain circumstances.

However, a pre-mixed option will not work for this plan. In that case an investor selects a pre-set asset allocation and when funds are withdrawn a little bit of each asset class is sold.

Final thoughts

Like any plan my approach is theoretical until it happens. Yet it has been road tested. I’ve managed my mother’s portfolio for the last 15 years. And this is the same plan I put in place for her transition to retirement. It is hard to ever declare a financial victory but so far so good. I’ve outlined some of the lessons learned from her transition to retirement here.

Coming up with a transition to retirement plan in your early 20s is a bit extreme. However, I was more than a bit bored and disengaged from my job. Unlike most of the things I did in my early 20s retirement planning was actually a productive exercise. The earlier you come up with a plan the better because it gives you time to refine it and be more thoughtful about your investment strategy. The last thing anyone wants is to wake up the first morning of retirement trying to figure out how to pay for it.

I would love to hear your own retirement plan. Email me at [email protected]

Get more Morningstar insights in your inbox