10 reasons owning your home beats super in retirement

Since the introduction of compulsory super, the industry has pushed its members to put as much as possible into super. It has been a disservice to anyone entering retirement who could have owned a home instead.

Opinion: Owning a home - with its tax-free status, exclusion from social security tests and spectacular price rises - has paid off handsomely for nearly every household over the long term.

While the superannuation industry implores members to put as much as possible into retirement savings, it is better to buy a home, especially for retirement. Owning a home is as much a lifestyle, security and self-determination decision as it is financial, and most Australians are willing to borrow to the hilt to join the party. The leverage has driven significant wealth creation, and the same people would never dream of borrowing such large amounts to buy shares.

In a speech to the National Press Club on 5 April 2023, Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe said:

“The price of land is high because of the choices we made as a society, where to live, how to tax housing and how to invest in transport.”

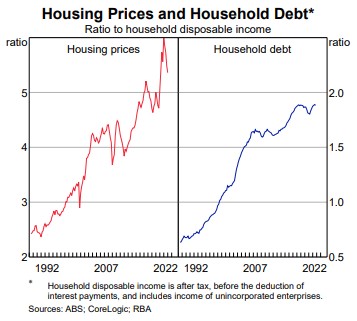

Successive governments have upheld policies making it highly attractive to own our homes, and it's unlikely to change. Over time, Australians have spent an increasing proportion of disposable income on housing, and the willingness to lock into 30-year mortgages sustains prices. Unfortunately, more people than ever cannot afford their own home, and it's made more difficult for them by deposits and income locked in superannuation.

Residential real estate in Australia is overwhelmingly owned by individuals rather than institutions and accounts for most personal wealth. Here are the market sizes:

- Residential real estate, $9.3 trillion

- Australian listed securities, $2.8 trillion

- Superannuation assets, $3.4 trillion

- Commercial real estate, $1.3 trillion

But this article is not about the merits of investing in residential real estate generally. It focusses on owning a home. If anyone with sufficient resources has the choice between owning their home and putting more money into superannuation, the case for the home is strong.

1. Ability to ignore market volatility

“Stocks provide you minute-to-minute valuations for your holdings whereas I have yet to see a quotation for either my farm or the New York real estate ... if a moody fellow with a farm bordering my property yelled out a price every day to me at which he would either buy my farm or sell me his – and those prices varied widely over short periods of time depending on his mental state – how in the world could I be other than benefited by his erratic behaviour? If his daily shout-out was ridiculously low, and I had some spare cash, I would buy his farm. If the number he yelled was absurdly high, I could either sell to him or just go on farming.”

- Warren Buffett.

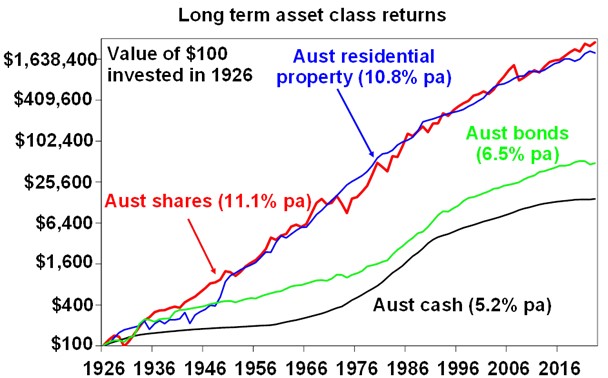

Given that the long-term returns from residential property are almost the same as returns from investing in local shares, as shown below, why are far more Australians willing to borrow to their maximum potential to buy a home? There are easy ways to gear into shares (geared ETFs, geared managed funds, margin lending, warrants, etc) but the daily mark-to-market of the portfolio is too painful for most to handle. Fortunately, when it comes to a home, despite what Warren Buffett says, nobody stands over the fence of a property and yells out a bid or offer each day. Homeowners hang on and benefit from long-term gains.

Source: AMP

Buyers of their own home have considerable risk tolerance because they think of it as their home first and a long-term investment second, and they are confident that over time, it will increase in value. Losses are not felt as long as mortgage payments can be sustained, and owners do not panic when the headlines scream 'Sharemarket loses $60 billion in a day' even if residential property prices fall 10% in a year, as they did to March 2023.

From 10am to 4pm every weekday except public holidays, the Australian stockmarket marks a portfolio’s scorecard. It tells investors how well or badly they are doing and drives much of the short-term mentality that plagues equity investors. Many equity investors do worse than the index because they buy when markets are high on confidence and sell when markets are low on doom. Research by DALBAR shows investor behaviour drives returns, with their 30-year data indicating the average investor in the US S&P500 achieved 7.13% while the index delivered 10.65%.

2. Australia’s short-term market and rental stress

My wife and I are friends with a couple in their forties who have two primary school children. We met them a few years ago when they lived near us. Their two-bedroom apartment was modest but within their budget, and the school was nearby. Then the landlord told them he was selling the apartment and gave them a month to leave. Stressed and desperate, they eventually found another affordable place but not with good transport, so they moved the kids to a closer school. This apartment leaked and as soon as the 12-month lease was up, they moved again. Overwhelmed by their nomadic existence, they bought a townhouse in the property boom of 2021 after watching prices spiral painfully upwards while they rented.

Contrast this with 1985 when I was working in Switzerland, and a Senior Vice President from Swiss Bank Corporation invited my wife and me to dinner. He proudly showed us around his grand home, including his books filling a library. A big oil tank in the basement to fuel the heating sticks in my mind. I asked him how long the house had been in his family.

“Oh, we don’t own it,” he said, sounding surprised by my question. “We have a 30-year lease. Why would anyone want to put all their money into a single asset like a house?”

Anybody? Try most Australians. Renters here face the insecurity of short-term leases and the potential to return to the market before they have settled in.

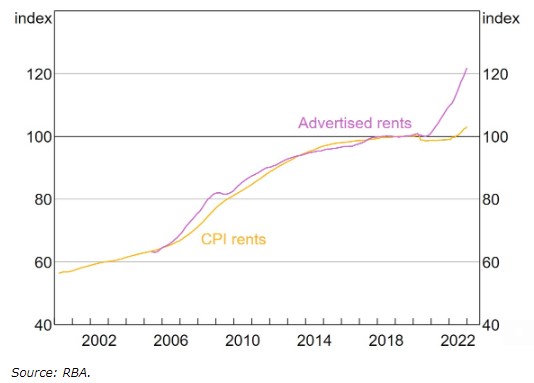

The National Debt Helpline reports that rent is one of the two most-reported worries, and the Reserve Bank has noted that renter stress and affordability are worsening as rents outstrip CPI and renters bid against each other. The cost of renting has become the second-highest component of the CPI.

CPI rents versus advertised rents (2019=100)

3. Humiliating renting experiences

Senior superannuation industry professionals argue the merits of super then return each night to a comfortable home where they can knock a nail in the wall without a real estate agent berating them.

Let’s put aside the financial aspects and consider what renting in retirement might look like. A 65-year-old is told to leave their home in a month, with the hassle of packing, storing contents, Saturday mornings inspecting new places, moving in, unpacking … and repeating all this a year later.

Here is what the landlord can do, according to NSW Fair Trading.

“A landlord, agent or authorised person acting on their behalf can generally only enter the property without the tenant’s consent if they provide notice to the tenant.”

Sounds fair, but what are these notice periods?

- To inspect the property: 7 days’ notice, up to four inspections a year.

- To assess for maintenance: 2 days’ notice.

- To repair a smoke alarm: 1 hour's notice.

And on it goes. If the property is for sale, the tenant must allow access twice a week on 48 hours’ notice and be given reasonable opportunity to move belongings to avoid being videoed or photographed. Check if the bathroom is clean? Please come right in. Imagine someone coming into your home and demanding you move your stuff for a decent photo of your bedroom.

It would take a lot of superannuation to want to go through that experience, then repeat it a year later when the landlord decides to up the rent by 50% or renovate the bathroom. No amount of admiring your superannuation balance compensates for being kicked out of your ‘home’.

4. More money needed by subsequent generations

Compulsory superannuation for most Australians was introduced in 1992, starting at 3% of salaries but escalating now to 10.5% on its way to 12%. In previous generations, much of this money would have gone into a home.

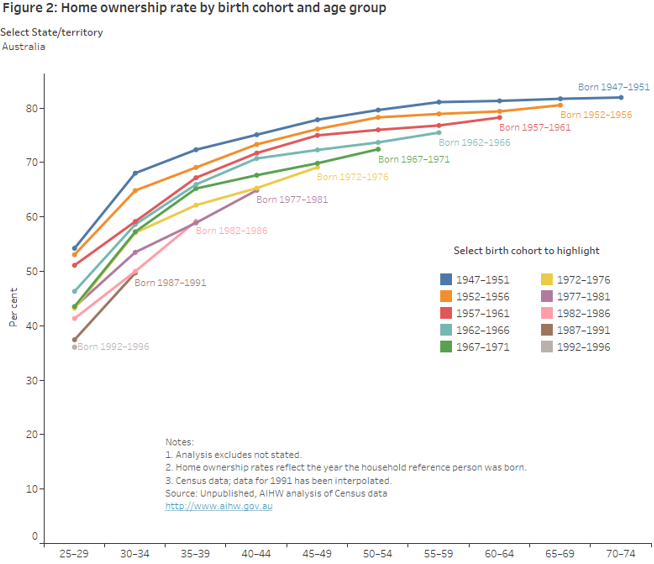

In 2021, according to the latest ABS data, of the 9.8 million Australian households, 67% were homeowners, of which 32% did not have a mortgage and 35% did. Home ownership is highest among older people, at around 80%, as younger people struggle to find the required deposits and income.

5. Housing shortages and greater competition for renters

Australia is facing a surge in population driven by high immigration levels, and at the same time, housing approvals are down. This chart from Westpac shows building approvals, and the vital number, 'Total dwellings', is down 31% from a year earlier.

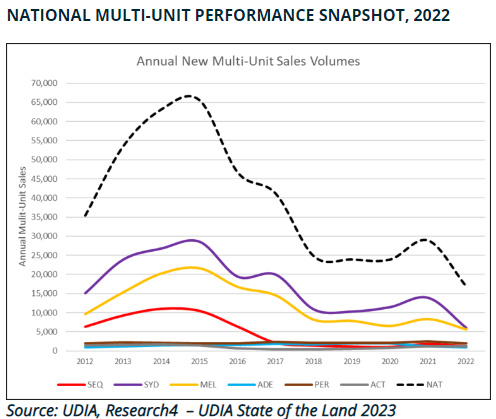

The National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation (NHFIC) estimates Australia will face a shortage of 106,000 dwellings by 2027, with 1.8 million new households forming in the next decade. Fewer apartments are being built, as shown below from Urban Development Institute of Australia (UDIA).

Thousands of building companies have collapsed in the last two years, and the most notable recent casualty, Porter Davis, left almost 2,000 homes unfinished.

According to CoreLogic, rents across Australia are 10.1% higher than a year ago, and vacancies are at record lows. Competition for scarce rental properties will only intensify in years to come as 650,000 migrants arrive over two years, with the biggest population rise in Australia's history at about 900,000.

6. Better tax breaks for homes than non-concessional super

While superannuation is lauded for its tax advantages, the only savings vehicle with a lower marginal tax rate than an own home is pre-tax (concessional) super, which is limited to $27,500 a year. For people on lower incomes, the tax in super of 15% may be higher than their marginal tax rate.

The chart below from the Grattan Institute shows the tax advantages of owning a home.

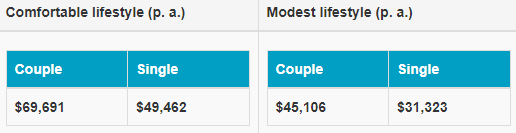

7. Home ownership assumed in retirement standards

The most-commonly referenced amounts required to live a comfortable or modest lifestyle in retirement are the ASFA Standards.

What is often overlooked is the short explanation in the footnotes to the tables, which is not even mentioned in the document showing the detailed break up:

“Both budgets assume that the retirees own their own home outright and are relatively healthy.”

So even the Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia (ASFA), the body representing large super funds and industry service providers, assumes home ownership before advising members how much money they need to meet a given lifestyle.

8. Social security incentives

The Principal Place of Residence (PPR) is excluded from capital gains tax on personal income and from asset eligibility tests for age pension and other social security pensions. However, superannuation assets are included, which means a person with a large super balance may not qualify for social security and the related health and pensioner benefits, but another person with the same value of assets held in a PPR qualifies. The full age pension for a couple with supplements is $1,604 a fortnight or $41,704 a year. That’s an annual incentive to buy a house rather than put more into super.

There is a concession to home ownership in the assets test. For example, a homeowner couple is eligible for a maximum age pension when assets are $419,000 or less (excluding the value of the home) whereas a non-homeowner couple is allowed a higher level of $643,500.

The Government even issues a sort of warning not to sell the family home. How much more privileged can an asset be?

“Your family home, if you live in it, isn't counted as an asset. However, if you decide to sell, it could affect your pension.”

9. An alternative source of money to live on

The Home Equity Access Scheme (HEAS, formerly the Pension Loan Scheme) allows homeowners to use real estate as security to generate retirement income. There are also many commercial home equity access schemes which offer different characteristics.

We have discussed the HEAS previously and the full terms are described here. A few key features are:

- The pension payment can be up to 150% of the maximum pension rate. That is $60,000 a year for a couple.

- It is available to people who are not on a government pension.

- There is a no negative equity guarantee, meaning the amount owed on the loan can never be greater than the market value of the property less any mortgage.

- Lump sum advances are possible.

Loan payments are only required from the estate or when the property is sold, and the current interest rate is an attractive 3.95%, although this may increase.

10. The value of 'psychic income'

In a world where it's easy to know the price of everything and the value of nothing, living in your own home carries considerable non-financial rewards. Economists call it 'psychic income' when pleasant surroundings, safety, security and even prestige contribute to wellbeing in a way not measured in money terms.

Once on the property ladder, especially in a house with land, there is often potential to invest in the value of the asset for personal use and financial gain. Fix the bathroom, install a new kitchen, build a sunroom and extra bedroom on the back - these are all great ways to invest in an asset over time, improving surroundings and lifestyle as financial resources and time allow. Many Australians have renovated their way to financial freedom after a modest start.

And here come some caveats ...

We could double the length of this article with qualifying statements, as every person is different.

Yes, some landlords reward good tenants, maintain their properties and rollover leases year to year.

Yes, new homeowners who bought at the peak in 2022 now face rising interest rates and mortgage stress. This article is not arguing everybody should own a home, as borrowers need the financial resources to service their debt.

Yes, the case for the most tax-advantaged, concessional amounts up to $27,500 a year into super is stronger than the non-concessional contributions from after-tax resources.

But, but ...

Arguments about the right time to buy could be made at many times in the last 100 years. The home I bought in 1989 was worth less four years later in 1993 (after 'the recession we had to have') but we did not sell until 2020. Baby Boomers did not pay 11 times earnings for properties but interest rates were far higher.

Renting in Australia is not a pleasant experience for many people. It is made more frustrating by successive government policies that have encouraged home ownership to such an extent that younger generations are locked out of the opportunity that their parents and grandparents took for granted.

As Governor Lowe said, that's the unfortunate reality of the system we have created. It would be political suicide, for example, to tax capital gains on a family home or include the PPR in the assets test for the age pension. No government will go there. The advantages of home ownership are unlikely to disappear, and it's more important for financial plans to consider the journey to home ownership than how superannuation should be invested.