The shortcomings of monetary policy

Monetary policy is a 'deeply flawed' way to manage the economy and yet we have not come up with anything better, says Morningstar's Graham Hand.

Democracy comes with troublesome flaws such as media influence, lobbyist access to politicians for favours, backroom deals, party politics and faulty personalities, but theocracy, autocracy or oligarchy are worse.

Democracy is dysfunctional but we have not come up with anything better.

Monetary policy is the same. It is flawed in its application but we have not devised an improvement, such that our central bank's attempts to fulfill its responsibilities under the Reserve Bank Act are blunt and imprecise. The Act says:

"Its duty is to contribute to the stability of the currency, full employment, and the economic prosperity and welfare of the Australian people."

Look up 'monetary policy' on the Reserve Bank's website and it says:

"The Reserve Bank is responsible for Australia's monetary policy. Monetary policy involves setting the interest rate on overnight loans in the money market (‘the cash rate’)."

That's mainly it. The cash rate, plus some activities on money supply. To contribute to the prosperity of the Australian people, the central bank weapon of choice is setting the cash rate. Consider some way this fails:

1. There are about 10 million households in Australia, but only one-third of them have a mortgage. Most people are not hit by higher mortgage payments, yet that is the primary inflation control mechanism.

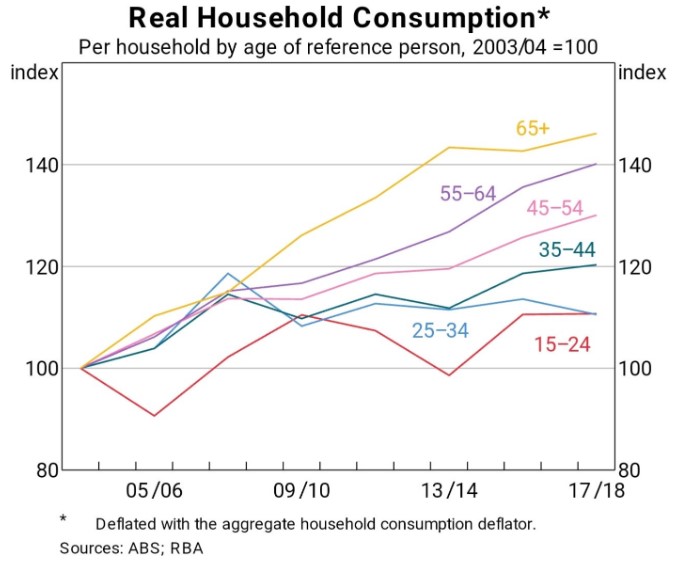

2. Increasing the cash rate stimulates the economy by boosting the nominal incomes of millions of Australians through higher term deposit and bond rates. If anyone argues it is not stimulatory because the older people who are the savers do not spend as much as younger people, consider this:

3. Fiscal policy often works in the opposite direction, as governments give cost-of-living relief when inflation rises, putting money into pockets when the central bank is trying to take it out.

4. Monetary policy is primarily demand-side economic management. It aims to expand or contract economic activity by controlling the cost of money. But in the current cycle, inflation is significantly driven by supply-side factors, such as Russia's war in Ukraine, the pandemic's impact on supply chains and natural disasters in Australia. None of which are sensitive to interest rate changes.

5. Rising cash rates feed into parts of the inflation calculation, the Consumer Price Index (CPI), generating an updraft. The Australian Bureau of Statistics advises:

"Housing is the highest weighted group in the CPI, accounting for around one quarter of the basket. It includes new dwellings purchased by owner occupiers (houses, townhouses and apartments), rents and major renovations."

Consider how supply shortages have driven up inflation, contributed to a decline in construction and rising rents. Says Bill Mitchell, Professor in Economics and Director of the Centre of Full Employment and Equity at the University of Newcastle:

"So we enter a ridiculous circularity. The RBA hikes interest rates. Rental inflation accelerates even though the other factors driving the overall CPI inflation trajectory are in decline. The RBA then claims the CPI inflation is not falling fast enough. The RBA hikes again … Rinse and repeat."

Borrowers who can least afford higher repayments are hit the most. Its doubtful they feel an increase in the cash rate 11 times in a year from 0.1% to 3.85% has improved "the economic prosperity and welfare of the Australian people".

The Reserve Bank and Governor Philip Lowe are acutely aware of the mental health implications of rising rates, and the Governor has made a point of meeting with suicide prevention agencies. The May 2023 Statement of Monetary Policy includes this acknowledgement:

"Community services organisations have raised concerns regarding the sharp increase in demand for their services over recent quarters, including for financial aid, domestic violence and acute mental health support, food bank services and housing assistance. They note that there has been a rise in the number of people seeking assistance for the first time, including renters and people with mortgages."

A policy which causes severe mental health problems for strugglers but puts more money in the hands of wealthy savers is a deficient way to control inflation. The Reserve Bank acted the worst when leaving the economic stimulus of 'whatever it takes' in 2021 as inflation was already taking hold. It poured fuel on the fire when it should have withdrawn oxygen.

This week's wage price index showed a rise at a decade-high 3.7% in the year to March 2023, and 0.8% for the quarter, both in line with expectations. After the release of the Reserve Bank minutes on Tuesday, CBA's Gareth Aird confirmed:

"Our central scenario puts the current 3.85% as the peak in the cash rate, while the near-term risk sits with another rate hike ... We continue to expect 50bp of rate cuts in Q4 23 and a further 75bp of easing in 2024 that would take the cash rate to 2.6% - a more neutral setting."