What drives investment results?

We look at key concepts such as return on capital and corporate culture to help you pick the next stock market winners.

Recently, I came across this great chart from a fund manager on what drives investment returns in stock markets.

The chart reveals that what’s likely to drive portfolio returns will depend on your time horizon.

What the chart doesn’t show is that your time horizon will often reflect your personality (as an individual investor) or institutional setting (as a professional investor/fund manager).

Let’s go through each of the drivers in the chart.

Sentiment change

The chart suggests that if you’re investing with a three-month time horizon, then you’re relying on a sentiment change in markets or a stock for your investment returns. I would suggest that this is mostly, though not entirely, accurate.

You might be a macroeconomic investor who can trade on how economic data will impact the stock market. For instance, an investor today may believe inflation in Australia will fall much faster than economists or bond markets expect. The investor might surmise that this will drive bond yields lower, and that long duration stocks – which have more earnings growth in the long term rather than short term – will benefit most. And the investor could potentially trade this to profit from it.

Another example comes from the time that I spent as a portfolio manager at AMP. There was a reputable quantitative fund at AMP that used to primarily trade on company earnings. It would identify companies whose earnings would soon be upgraded, and the fund guessed that this would lead to these stocks outperforming the market. It was a short-term, profitable strategy.

There are other short-term trading methods which don’t involve a sentiment change. For example, arbitrage. A simple example of arbitrage is if a stock trades in different countries yet is valued and priced differently. The arbitrageur may bet on the gap in valuations closing, usually driven by an event as a catalyst.

Legendary investors such as Ben Graham and Warren Buffett have successfully used this type of strategy. The modern-day investment giant, Jim Simons, whose main fund is reported to have earned 66% per annum over 30 years, has employed arbitrage as part of his investing toolkit.

Multiple change

The chart also suggests that if your time horizon is around one year, you’ll often be looking for a change in stock valuations to drive your investment performance. Put simply, you can buy Westpac (WBC) at the current 12-month forward price-to-earnings multiple of 10.25x and sell it in one year’s time if the multiple reaches 12x. Combined with any earnings growth, the multiple uplift would result in a nice overall return.

What increases or decreases valuation multiples? On a one-year view, it can be any manner of things: an event (buy backs, increased dividends, economic datapoint), earnings, economic environment, to name but a few.

The chart probably isn’t fair to value investors as many of these investors have 3-5 year strategies, where multiple change is a key driver, though not the only one.

Value investors also sometimes combine buying depressed valuation multiples with the purchase of a depressed stock/sector. For example, I have little doubt that value investors have run their eyes over the Australian office property sector. This sector has been hit by the work-from-home trend and higher interest rates which impact valuations (their so-called cap rates) and earnings (via higher interest costs). Several office property stocks are trading at large discounts to their asset values. A value investor may believe that these discounts are unwarranted as the cycle will improve from here. If right, earnings may improve from their current downtick and the valuation discount may narrow or be eliminated over time.

Cycle/industry

Businesses and business sectors move in cycles. There are fund managers who look at sectors and bet on a sector turnaround by buying key companies in that sector. Instead of focusing on one stock, they might spread their bets on several stocks to play the turnaround that they expect. Or they may narrow it down to just a single stock that they think will be the largest beneficiary of any sector uplift.

Sector turnarounds happen all the time. When the Covid pandemic first broke, airlines, hotels and tourism stocks cratered. Though it’s taken several years, these sectors did recover and, ironically, are now among the high-flying segments of the stock market. This shows you how market sentiment on industries can shift over time.

Return on incremental invested capital

The chart also indicates that investors with a 5–10-year time horizon will often look at return on incremental invested capital, or ROIIC, to drive investment results.

Before getting to this fancy investment term, it’s important to note that the chart suggests that sentiment change, multiple change, and the business cycle/industry are less important on a long-term time horizon. And that ROIIC is more critical.

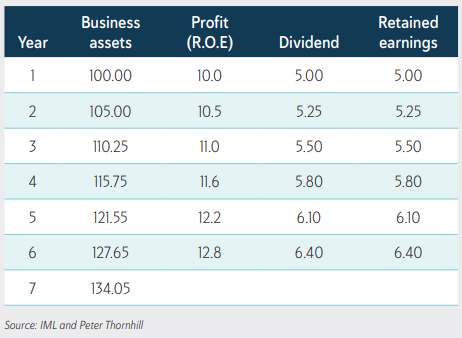

To see why, let’s look at how earnings are compounded in a business. Take a company called ABC which has $100 in assets and makes a return on those assets of $10 in year 1, equating to a 10% return on equity. ABC pays out 50% of those earnings, or $5, as a dividend. And it holds onto the other $5 as retained earnings.

By year 2, ABC has $105 in assets ($100 of initial assets plus $5 in retain earnings), and it again earnings a 10% return on the assets, which comes to $10.5 in profit. Again, ABC pays out 50% of those earnings, equating to $5.25 as dividends. The retained earnings are then $5.25.

By the end of year 6, earnings have compounded to reach $12.80, while dividends have grown to $6.40, and assets have increased to $134.05.

This shows the power of returns on equity, though it takes time for positive business results to compound.

Like all investment metrics, return on equity comes with weaknesses. The key one is that it can be increased through a company taking on more debt. Debt in and of itself isn’t a bad thing. But whether it’s a little or a lot, any leverage increases business risk.

That’s why some investors prefer ROIC, or return on incremental capital, to measure business results. ROIC is the profit a company makes on both its equity and debt. The measure specifically takes debt into account when measuring returns.

ROIC also has drawbacks. ROIC measures profit on capital (debt plus equity) that may have been invested over many years. Sometimes, decades ago. But an investor is less interested in what returns a company generates in the past than what it will earn in the future. To determine this, they’ll want to look at the rate of return a company has generated on incremental investments recently.

Investor John Huber provided a good example of this via the stock, Walmart (WMT), in 2016. At that time, Walmart earned $14.7 billion of net income on roughly $111 billion debt and equity capital, or about a 13% return on capital.

That seems pretty good on the face of it. However, Huber wanted to know how the company had performed more recently and this is what he found:

“In 2006, Walmart earned $11.2 billion on roughly $76 billion of capital, or around 15%.

In the subsequent 10 years, the company invested roughly $35 billion of additional debt and equity capital (Walmart’s total capital grew to $111 billion in 2016 from $76b in 2006).

Using that incremental $35 billion they were able to grow earnings by about $3.5 billion (earnings grew from $11.2 billion in 2006 to around $14.7 billion in 2016). So in the past 10 years, Walmart has seen a rather mediocre return of about 10% on the capital that it has invested during that time.”

In other words, Walmart’s ROIC at that time was 13% yet it’s ROIIC was 10%, and the latter was likely to be a truer indication of what future business performance may look like.

These concepts of ROE, ROIC, and ROIIC are important for long-term investors. Don’t take my word for it: here’s Warren Buffett on the topic:

“Growth benefits investors only when the business in point can invest at incremental returns that are enticing—in other words, only when each dollar used to finance the growth creates over a dollar of long-term market value. In the case of a low-return business requiring incremental funds, growth hurts the investor…

Leaving the question of price aside, the best business to own is one that over an extended period can employ large amounts of incremental capital at very high rates of return. The worst business to own is one that must, or will, do the opposite—that is, consistently employ ever-greater amounts of capital at very low rates of return. Unfortunately, the first type of business is very hard to find: Most high-return businesses need relatively little capital. Shareholders of such a business usually will benefit if it pays out most of its earnings in dividends or makes significant stock repurchases.”

And here’s his offsider, Charlie Munger:

“Over the long term, it's hard for a stock to earn a much better return that the business which underlies it earns. If the business earns six percent on capital over forty years and you hold it for that forty years, you're not going to make much different than a six percent return—even if you originally buy it at a huge discount. Conversely, if a business earns eighteen percent on capital over twenty or thirty years, even if you pay an expensive looking price, you'll end up with one hell of a result.”

Morningstar has its own view on the topic. Its analysts focus on identifying moats or sustainable competitive advantages. While the assessment may be qualitative in nature, the financial statements of a company will reflect the impact of the sustainable competitive advantage. A company with a moat will have an ROIC that exceeds the weighted average cost of capital (‘WACC’). In layman’s terms, it means the company generates a return by investing in the business that exceeds the cost it takes to raise capital. If a company can earn a 10% return and it can raise capital at 7%, the difference will accrue to investors over time.

People/culture

The lead chart in this article highlights the important role that people and culture in a company have on investment returns over a +10-year period. These things can’t be measured; they’re qualitative, not quantitative.

The best example that I can think of about the importance of corporate culture is American retail wholesaler, Costco (COST). Costco has a fascinating business model that will be studied by investors for many decades. It buys goods in huge quantities and then sells them at cost to customers. It makes almost no profit from the selling of the goods.

How it makes money is through memberships. In Australia, the annual membership is $60. What a customer gets for this membership is access to cheap goods in bulk, and an international range that can’t be matched by local suppliers.

Costco has immense power over global suppliers given its customer base, and its customers are happy with the bargains they get.

However, the business model wouldn’t work as well without an energized and effective workforce. Unlike Walmart which has historically paid employees the minimum wage, Costco has made it a policy of paying well above minimum wage rates. It figures that this will not only motivate employees but incentivize them to stay at the company for the long-term. This has the bonus of reducing costs associated with the hiring and firing of staff.

While Costco has a beautiful business model, much of its success can be attributed to its culture. And that success has flowed through to investors.