It's coming: 10 ways to cool rampant housing prices

IMF, OECD, RBA, APRA, CFR, CBA and ANZ are all calling for curbs on housing lending. Why will it take APRA months to issue a paper?

It’s finally coming. After watching house prices surge around 20% in a year in many parts of Australia (and Sydney 23%), Treasurer Josh Frydenberg has signalled action to control rampaging prices and potential financial instability threats.

Although prices are rising around the world, when it comes to citing a prime example, even The Wall Street Journal turns to Sydney. On 27 September 2021, it reported:

“In cities from Austin to Dublin to Seoul, more families are finding it impossible to pay higher prices unleashed by a global property boom. Sydney house prices leapt by nearly $870 a day in the second quarter of the year, said real-estate firm Ray White. In the U.K., first-time buyers are paying on average 32% more than 12 months ago, according to Benham and Reeves, a real estate agency.”

Australia’s regulators, notably the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) and the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), have been slow to respond. Both deny responsibility. Governor Phillip Lowe recently said higher house prices are "outside the domain of monetary policy and the central bank", although Assistant Governor Michele Bullock later said: "developments in the housing market (including prices) provide information on the emergence of financial stability risks".

It’s time to act, not only for financial stability reasons and because borrowers are taking on too much debt, but a generation of Australian families are increasingly priced out of the home market.

Shane Oliver of AMP Capital and I recently appeared on Saturday Extra on Radio National, and Shane addressed the intergenerational social tensions:

“I think it’s grossly unfair … We can’t organise our property market in a way that makes it affordable for younger people without massive amounts of debt. This is a major social problem. The longer we leave it, it will lead to rising discontent and we’ve seen what that leads to in the US.”

There are plenty of policy choices capable of taking the steam out of the market. Clearly some of these are politically difficult but that does not mean they should be ignored.

1. Introduce macroprudential controls

Australian banks are more generous than their peers in other countries on standards for housing lending. A recent Macquarie Research Report said Australian banks are willing to lend at about seven times a borrower’s gross income (and up to nine times with senior approval) versus around four or five in places like the UK, Canada, the US and Sweden. In Australia, 22% of loans have a debt-to-income ratio of six and over according to APRA, a rapid rise in the last year. Macquarie also reported that about 38% of borrowers (on a weighted average basis) took on debt at their maximum capacity in FY21.

This chart from CoreLogic shows macroprudential limits can reduce housing prices, such as when the Hayne Royal Commission supported strong responsible lending laws and when limits were placed on interest-only loans.

Josh Frydenberg finally accepted the need to tighten the reins, telling The Australian Financial Review:

“... it is important to continually assess the appropriateness of our macroprudential settings. We must be mindful of the balance between credit and income growth to prevent the build-up of future risks in the financial system. Carefully targeted and timely adjustments are sometimes necessary. There are a range of tools available to APRA to deliver this outcome.”

The International Monetary Fund also weighed into the debate, advocating the need for debt-to-income ratio or loan-to-value ratio caps on mortgage lending.

“Surging housing prices raise concerns about affordability and financial stability ... Macroprudential policy should be tightened and lending standards closely monitored.”

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand acted along these lines as their house prices rose rapidly, also favouring debt serviceability restrictions to meet its housing price stability goals.

“Our analysis detailed that debt serviceability restrictions, such as a debt-to-income (DTI) limit, are likely to be the most effective additional tool that could be deployed by the Reserve Bank to support financial stability and house price sustainability."

So DTI is shaping up as a target. DTI is total debt divided by gross income (before tax). ANZ and NAB cap their DTI at nine, while CBA and Westpac allow above seven with special approval. What does this mean? If two people earn $100,000 each, that’s $200,000 gross income before tax. With a DTI of nine, they can borrow $1.8 million. Throw in their own savings and generous assistance from the Bank of Mum and Dad, and that’s why many buyers have $3 million to spend.

2. Increase the ‘floor rate’ or ‘buffer’ used to assess repayment capacity

At the moment, APRA requires banks to calculate borrower repayments at 2.5% above the interest rate charged. Alternatively, the bank can set a ‘floor rate’, and use whichever rate is higher. APRA previously imposed a floor rate of 7% but it was removed in 2019 as it was seen as a major limit to borrowing capacity.

Although borrowers might look at a stated lending rate of 2% and calculate for every $1 million they borrow, the repayment is only $20,000, banks use different rates to provide an affordability buffer and to cover future rate rises. CBA Managing Director, Matt Comyn, advised the Senate Economic Committee last week that his bank is increasingly concerned about the mortgage stress on its customers, and he supported ‘modest’ measures to control house prices. He added:

“We have put up our benchmark floor rate to 5.25% which is well above the rate customers would pay.”

One reason Matt Comyn voluntarily increased the floor rate is that he considers loan-to-valuation hits first home buyers as they have not built up enough of a deposit to justify the loan size, whereas they may have the future servicing capacity to pay the loan.

3. Tighten lending standards

The Macquarie Research Report estimates Australian banks offer their clients between 35% and 65% more than their global peers. Adding to the concerns around high debts are doubts about the accuracy of mortgage applications.

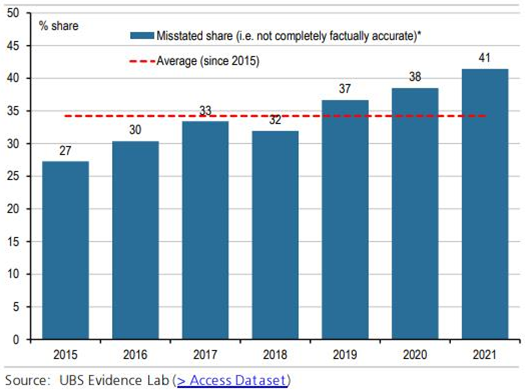

UBS’s Evidence Lab surveyed 900 Australians who took out a mortgage in the last year, looking for "factually inaccurate" mortgage applications. The 2021 Report “suggests a material deterioration in lending standards” with the share of misstated applications rising to 41% from 38% in 2020 and 27% in 2015. Application errors included over-statement of income and assets and an under-statement of financial commitments and living costs.

Share of home loans misstated (not factually accurate)

UBS also reported the time for approval had lengthened, but this was more likely due to the record volume of loans rather than tighter lending standards.

ANZ Managing Director, Shayne Elliott, also speaking to the Senate Economics Committee, said:

“We’re taking more time to be careful, to ask more questions, to really assess whether people do have the capacity to take on the debt that they would like. In our case, we’ve lost a bit of market share … as a result of that, but it’s just a time to be prudent and a bit more cautious.”

4. Overhaul planning rules and land availability

The IMF also suggested Australia could improve housing supply and affordability, with new infrastructure provisions to address scepticism about new developments.

This view gained some support from Philip Lowe, who said rising housing prices should be addressed through changing the factors that influence the value of land:

“More broadly, society-wide concerns about the level of housing prices are not best addressed through increasing interest rates and curbs on lending. While monetary policy is contributing to higher housing prices at the moment, the way to address these concerns is through the structural factors that influence the value of the land upon which our dwellings are built. The factors include: the design of our taxation and social security systems; planning and zoning restrictions; the type of dwellings that are built; and the nature of our transportation networks. These are all obviously areas outside the domain of monetary policy and the central bank.”

The Chair of the current Inquiry into Housing Affordability and Supply, Jason Falinski, has made his views clear, saying:

“the research points to limitations on land and restrictive planning laws as the major causes of shortages in supply.”

However, this opinion is not universally supported, as the vast majority of sales are existing houses in major cities. How does a new land release 50 kilometres from the CBD improve affordability in the inner city?

5. Review the role of the RBA in housing policy

Australia has a complex mix of official bodies with some clear and some overlapping responsibilities. The Council of Financial Regulators (CFR) chaired by Governor Philip Lowe also includes the heads of APRA, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission and Treasury, and it meets quarterly to improve coordination and discuss policy. House prices were on the agenda last week, and under Josh Frydenberg’s direction, the group has been charged with looking at policy solutions.

The above quote from Philip Lowe on "areas outside the domain of monetary policy and the central bank” shows he believes interest rates and curbs on lending are not the best moves to control prices, and other factors are more important.

But Michele Bullock said in an online speech:

“Sharp rises in housing prices that are not associated with fundamentals could lead to instability by raising the risk of a subsequent decline. Whether or not there is need to consider macro-prudential tools to address these risks is something we are continually assessing.”

Last week, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) said the RBA had missed its key targets in recent years and its operations should be reviewed. Josh Frydenberg is open to the idea, and it should be clarified whether the RBA has any responsibility for housing prices, especially in the context of financial stability.

6. Lightly tap the interest rate brake

Interest rates are set at levels which are appropriate for the entire economy, including business borrowing, and cannot be used solely to reduce house prices. Governor Philip Lowe’s recent speech set jobs growth as a far more important goal:

“I would like to address the question of housing prices, as some analysts have suggested we might lift the cash rate to cool the property market. I want to be clear that this is not on our agenda. While it is true that higher interest rates would, all else equal, see lower housing prices, they would also mean fewer jobs and lower wages growth. This is a poor trade-off in the current circumstances.”

To the extent that the Fear of Missing Out drives rising property prices, there is probably no greater measure than a slight tap on the interest rate brake. A rise from the current 0.1% to 0.2% would send a signal. However, Lowe is looking to other members of CFR to do the housing price work. Confirming other steps are coming:

“That is not to say that there aren't public policy issues to be addressed here. On the financial side, the issue is the sustainability of trends in household borrowing. We are continuing to watch this closely, with the Council of Financial Regulators discussing possible regulatory steps if lending standards deteriorate or credit growth accelerates too much.”

7. Maintain responsible lending rules

Josh Frydenberg has flipped around on responsible lending rules. The Hayne Royal Commission made the retention of these laws its first recommendation after much evidence that banks had engaged in predatory lending, making loans to people who had no chance of repaying. ASIC mounted the so-called 'wagyu and shiraz' action against Westpac in 2017 to prove it had ignored responsible lending laws prior to 2015 but the lawsuit was unsuccessful.

The Treasurer initially supported the Hayne recommendations strongly, but he later argued access to credit had become restrictive and was compromising economic activity. He said:

“What began as responsible lending principles has translated into a practice that has become imbalanced between a lender and its customer, leading to the undesirable consequence of unduly restricting lending.”

He introduced legislation to repeal the responsible lending laws in September 2020 but they did not pass through the Senate.

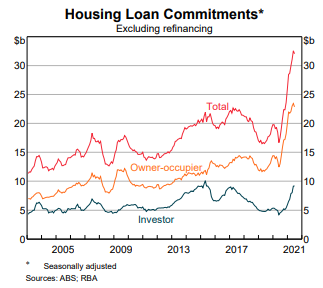

There’s not much evidence that lending has been restricted. All the signs are the opposite, that access to mortgage credit is relaxed and lending is surging, as shown below from the RBA Chart Pack. Housing loan commitments have surged in the last year.

8. Examine a wide range of tax and welfare rules that benefit property

Australia’s tax and social security system strongly favours home ownership and investing in residential property. Many of these policies are sacred ground for homeowners and investors, and there are plenty of Australian politicians with investment property on their personal interests register.

Much good policy is politically difficult, which is why small policy targets have become smart politics. The Labor Party proposal to reduce the capital gains tax discount taken to the last election has now been abandoned.

Without elaborating in detail, consider:

- Exemption of Principal Place of Residence (PPR) from capital gains tax.

- Exemption of PPR from age pension asset test (a subject discussed extensively recently with an unprecedented response, including an article viewed over 30,000 times).

- Negative gearing allows losses from investment property to offset other income, whereas losses from business must be carried forward.

- Where a PPR is passed to the next generation, there is no capital gains tax if the asset is sold within two years.

New Zealand passed laws in March 2021 to curb price increases including the removal of tax deductions for interest payments on investment property loans.

9. Talk it down

For all the controls and changes the regulators and governments could bring to housing policy, it is the mood and perception of buyers and sellers that drives panic buying. I have written previously about attending inspections and auctions recently where price guides are smashed by half a million on houses that need a lot of money spent on them. Supply is at record lows during lockdowns, and in the current market, few people want to sell before they buy in a fear of missing out.

In a FOMO market, signalling from the Treasurer and Government officials that they would prefer to see price stability and avoid future stress might release some pressure.

There is too much complacency by borrowers taking massive debts. Digital Finance Analytics claims half of borrowers hold too much debt for their income, and their modelling suggests a 0.5% rise in interest rates would increase the number of households facing mortgage stress by 220,000 to 1.7 million families. Interest rate will rise at some time, and it's better to issue warnings now than face rising foreclosures in the future.

10. Move quickly

The CFR issued a statement following its 24 September 2021 meeting. It confirmed action is coming on macroprudential controls but with little immediate policy change:

"The Council is mindful that a period of credit growth materially outpacing growth in household income would add to the medium-term risks facing the economy ... Over the next couple of months, APRA also plans to publish an information paper on its framework for implementing macroprudential policy."

But it's a mystery why APRA needs another two months. In March 2021, six months ago, the Chair of APRA, Wayne Byers, told a Parliamentary Committee that it was watching key metrics while deciding if macroprudential intervention is required. But then he added:

“It’s not our job to solve house prices and it’s not our job to solve house pricing affordability.”

If it's not the responsibility of the RBA or APRA, whose is it? Given substantial support for greater controls, even among banks themselves, the delay brings further dangers. Already, buyers' agents are encouraging clients to rush into the market before APRA strikes. This will make the indebtedness and financial vulnerability worse while APRA thinks about it.

Even when all the ducks are in a line, nobody wants to pull the trigger.