Benefitting from the idea of numbers over narrative

If a widely held view turns out to be wrong or exaggerated, investors taking the other side of the bet can be rewarded.

The phrase “numbers over narrative” isn’t mine.

In my world, anyway, that honour belongs to my old colleague and friend Stephen Clapham, an ex-hedge fundie who now teaches analysts to pick apart balance sheets. Steve uses this phrase a lot, so I hope he doesn’t mind me borrowing it for the purpose of this article.

That purpose is to think a bit about what goes into a company’s stock market valuation and therefore its price on a per-share basis. We’ll also look at a situation where media headlines and general investor sentiment may be wrong on one of the key inputs.

What decides a valuation?

The smart-ass’s answer would be that a stock’s value is simply the price at which buyers and sellers were last willing to do a deal. That may be so. But I want to go a few levels deeper and ask what is encapsulated in that price.

This involves asking why an investor would want to buy a share in the first place. And to do that, let’s cast aside speculation and pretend that every purchase in the stock market is made in the way it was intended:

The buyer wants to purchase a long-term ownership stake in a real business.

To achieve this, the investor lays out cash today for an equity interest that entitles them to a fractional share of the profits generated by the business until the owner sells those shares.

The hope here, of course, is that the owner will eventually recoup more cash than was initially layed out – either in the form of dividends or as earnings retained and reinvested by the company.

Approaches like discounted cash flow and dividend discount models might tackle this question from a different angle or by using a different data point. But they all require the investor to ask the same basic questions:

- How much cash can the business be expected to generate for owners in the future?

- How long can the business keep delivering the expected level of cash generation?

- What is the likelihood that the cash flows can grow over time?

- How fast can the cash flows grow? And for how long?

- How sure can I be that the business will generate the amount of cash I am predicting?

Of course, the market’s collective opinion on these questions aren’t the only thing that influence stock prices. In the real world, prices are also influenced by greed, fear, excitement, depression, FOMO and even disgust felt by investors at the time.

When will the party end?

Let's return to the question of how long a company can keep churning out profits at a certain level.

Several things could impact your opinion on this. But let’s keep it simple and focus on just two: the viability of a company’s industry a few years out and the company’s competitive position within it.

All other things being equal, it makes sense that a competitively advantaged company in an industry with solid long-term prospects will command a higher price than a company with no moat selling a highly cyclical product that might be obsolete soon.

In a shamelessly cherry-picked example, consider the average forward P/E of Nestle versus Whitehaven Coal over the past five years. Nestle has traded at an average of 22 times and Whitehaven has traded at closer to 4 times. Why?

One explanation is that investors have greater certainty over the durability of Nestle’s cash flows beyond the next few years. They are therefore willing to pay a bigger multiple of annual earnings and wait longer to recoup their initial outlay.

The contrarian’s opportunity

A potential opportunity could arise, then, if a widely held view on an industry’s medium to long term prospects is 1) depressing valuations and 2) could prove to be incorrect or exaggerated.

One example might be the general perception of oil and gas companies. As countries continue to make big net zero pledges and invest heavily in other sources of energy, a lot of people might be tempted to view oil and gas as an industry on its way out.

This perception could be aided by forecasts like those from The International Energy Agency, which has stuck to its prediction that oil and natural gas demand will peak by 2030 and decline from there.

If that forecast proves to be correct, hats off to the IEA. Because it appears to be a very bold call.

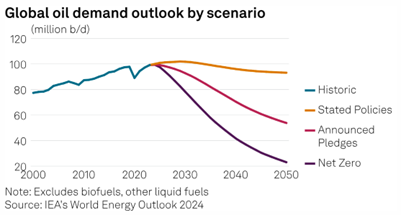

Take the IEA’s prediction for global oil demand, for example. The blue line on the chart below shows historic demand and the other lines show the IEA's forecast for demand based on different net zero policy scenarios:

Figure 1: IEA global oil demand projection. Source: S&P, IEA World Energy Outlook 2024

You can see that the blue line (showing total oil demand) has only really gone down twice since 2000: once in the GFC and once during Covid, when the world literally shut down. That's a pretty solid track record of demand growth.

Yet the IEA, whose forecasts are widely respected and quoted, think global oil demand will peak before 2030 and could erode rather quickly if climate pledges become policies that are followed through.

How realistic is the latter scenario, though? It is a lot easier to make a pledge than to actually make it policy. And it is a lot easier to say that you are going to consume fewer oil and gas based products than actually doing it.

The thought of peak oil demand by 2030 also appears to be a bold call when you consider:

- Earth’s population is estimated to grow from around 8 billion in 2022 to over 10 billion by 2050

- Developing economy GDPs will likely continue to rise, and people living in those countries probably want to enjoy more of the energy-intensive luxuries that we enjoy (like air travel)

- Many petroleum-based products that we rely on aren’t easy to supplant quickly (or, in many cases, at all)

- Most of the demand and population growth is coming from emerging economies, where the IEA have said that clean energy sources "have had a harder time" replacing fossil fuels

In our Q4 equities sector outlook, Morningstar Australia's energy analyst Mark Taylor made many of the points above and said that oil demand looks likely to grow "for years" from here and expects “little decline in demand by 2050".

He is similarly optimistic on the medium-term demand picture for natural gas, which could benefit from similar tailwinds and also take up some of thermal coal’s slack in regards to baseload power generation.

This paints a very different picture to headlines portraying oil and gas as an industry on its way out. And if those headlines are compressing valuations in the sector, investors willing to take a different viewpoint could stand to benefit.

Consider the following highlights from one ASX company's latest research report on Morningstar Investor:

- Strong global demand outlook for the company's main products lines

- Promising new projects supporting growth

- Double-digit annual increase in earnings per share forecast over next 10 years

Without the rather big hint that this concerns an oil and gas company, you might think I’m talking about Nestle again. But I’m actually talking about Santos, a company that few people would think of as having a compelling growth story.

With a forward price-to-earnings ratio of little more than 9 times, a trailing dividend yield of over 6% and a stock price around 45% below Mark Taylor’s Fair Value estimate, Santos trades at a valuation to match that pessimistic view.

How can it be?

You might be wondering how such a discrepancy between price and our estimate of Fair Value could arise in such a large, mature company.

Obviously there are always several factors to consider, but I think Mark’s numbers over narrative approach to weighing up the oil and gas industry's medium term prospects play a big role here.

As he said in his sector outlook, "efforts to decarbonise global energy supply is naturally a key concern for investors when considering hydrocarbons. But oil demand is not going anywhere anytime soon".

It's also worth noting that Taylor's valuations for Santos and other oil and gas companies aren't even reliant on high commodity price estimates. For example, his valuations currently assume a mid-cycle price of USD 60 per barrel of oil versus prices of around USD 80 today.

More articles from Morningstar:

Get Morningstar insights in your inbox

Terms used in this article

Fair Value: Morningstar’s Fair Value estimate results from a detailed projection of a company's future cash flows, resulting from our analysts' independent primary research. Price To Fair Value measures the current market price against estimated Fair Value. If a company’s stock trades at $100 and our analysts believe it is worth $200, the price to fair value ratio would be 0.5. A Price to Fair Value over 1 suggests the share is overvalued.

Moat Rating: An economic moat is a structural feature that allows a firm to sustain excess profits over a long period. Companies with a narrow moat are those we believe are more likely than not to sustain excess returns for at least a decade. For wide-moat companies, we have high confidence that excess returns will persist for 10 years and are likely to persist at least 20 years. To learn more about how to identify companies with an economic moat, read this article by Mark LaMonica.