3 history lessons, and being humble

Three historical episodes in stock markets and what they can teach you about becoming a better investor.

At the start of 1942, things were gloomy for Western countries. Yes, the US had officially entered World War Two in December of the previous year, yet the war wasn’t going well. The Japanese seemed invincible as they roared across the Pacific, even reaching Darwin in February of 1942. The Germans were progressing in their offensive in Russia and the British were having continual setbacks in the Middle East.

Stocks markets floundered. February 1942 was the slowest month of trading on US markets since 1915. The median price to earnings ratio of 600 representative stocks in the US was just 5.3x, and only 10% of all stocks traded at more than 10x the previous year’s earnings. 30% of the US market trading at less than 4x earnings. And dividend yields on shares were 3 times greater than bond yields. By the end of April 1942, the US market was already down 20% for the year, and 31% lower than the high reached in 1941.

Then, something happened. As Barton Biggs recounts in his book, Wealth, War & Wisdom, the US market bottomed on April 30, 1942, and it became a bottom for the ages. The remarkable thing is that the market bottom happened before the war started turning in favour of Western forces.

At the Battle of the Coral Sea in early May, Japan’s advance on Port Moresby had been halted. It was the first time that the Japanese had been denied in the Pacific and it showed that US forces could match them. Yet, the battle was more of a draw than a win.

Then came the outright victory at Midway in early June, which turned the tide of the war.

The US stock market went on an epic four-year bull run. From April 30, 1942, to the end of 1945, the Dow Jones Industrial Average climbed 105%. US small cap shares leaped 45% in 1942, 88% in 1943, 54% in 1944, and 75% in 1945.

Lesson 1: Stock markets are more prescient than you think.

In his book, Principles for Dealing with the Changing World Order, hedge fund tycoon Ray Dalio conducts a thought experiment. He says imagine you went back in time to 1900 without any knowledge of what was to come, and you wanted to invest. One way to do it would be to observe the top 10 great powers of that time and invest in those nations. You would think that these would be safe, prosperous, and profitable places to invest. Yet, Dalio notes:

“Seven of these 10 countries saw wealth virtually wiped out at least once, and even the countries that didn’t see wealth wiped out had a handful of terrible decades that virtually destroyed them financially.”

A 60% equities and 40% bonds portfolio proved anything but safe.

The likes of the US and Australia escaped the fates of these countries, largely by being on the winning side of wars. Subsequently, Australian stock market returns have been among the best in the world.

And America has gone from a rising power to a dominant one.

Dalio’s point though is that history is never static and neither is wealth.

Lesson 2: Past performance isn’t indicative of future performance, and plan accordingly.

Inflation is falling across the developed world and many economists and some central bankers are declaring victory.

But in the last great inflationary episode during the 1970s, inflation dipped sharply on three different occasions before rising to higher peaks.

The narrative in the US and Australia is that interest rates were kept too low during the ‘70s and that’s part of the reason that inflation kept coming back.

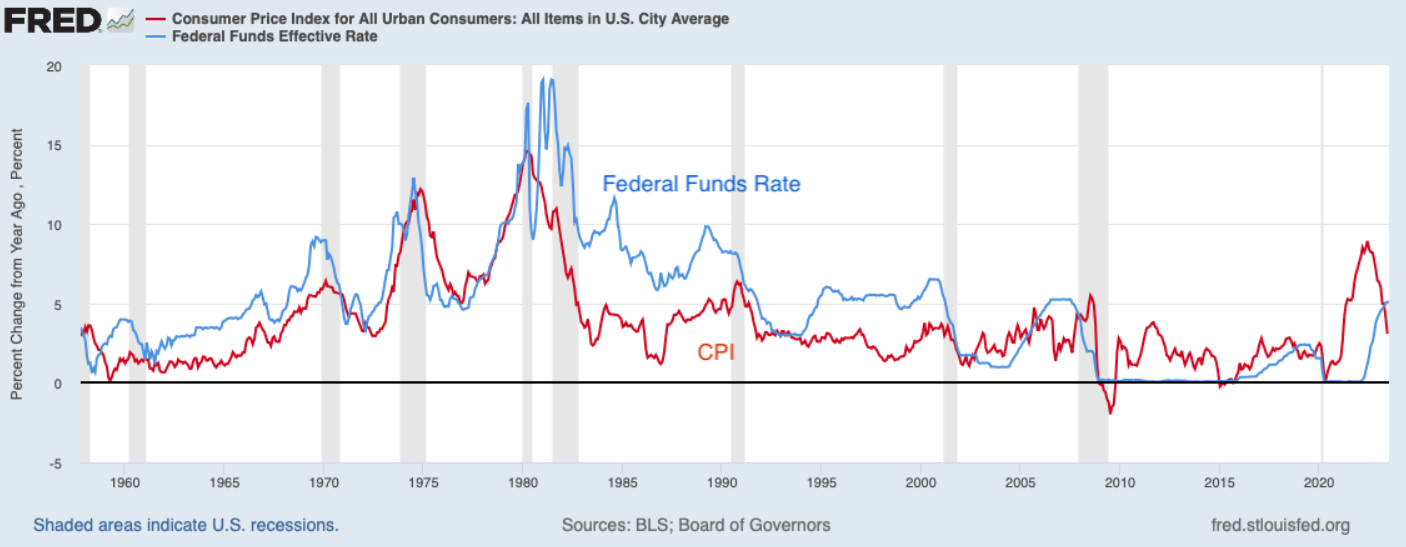

Yet, as Stanford University Professor John Cochrane suggests, that narrative doesn’t seem to fit reality. As the chart below shows, the US Federal Reserve continuously hike rates and rates were often above the inflation rate during the 70s (positive real rates). But the rate increases didn’t seem to quell inflation for good.

It took interest rates of 20% when inflation reached 15% in the early 1980s before the inflation dragon was slayed. The interesting part about this is that economists even now talk about the ‘lag effect’ where rate moves impact inflation up to two years later. Yet, the early 80s rate hikes had an almost instantaneous effect on inflation.

Lesson 3: Inflation is complex, and its future direction is difficult to predict.

James Gruber is an assistant editor at Firstlinks and Morningstar.com.au