Preparing for the worst-case scenario

One of the best ways to build and maintain an investment portfolio is by stress testing different scenarios, including the worst-case.

Mentioned: Woolworths Group Ltd (WOW)

Investors are an optimistic bunch. Naturally, we think of a brighter future, where assets appreciate and compound our wealth. To think otherwise doesn’t make sense as there’d be little reason for us to invest.

Yet here’s a counterintuitive point: one of the best ways to build and maintain an investment portfolio is by thinking about the worst-case scenario.

Before you suggest that I’ve lost the plot, know that none other than Charlie Munger, Warren Buffett’s offsider, has my back on this point. Well, sort of.

Munger has famously guided his followers to “invert, always invert”. By this he means that many problems can’t be solved by just thinking ‘forwards’, or toward the next logical step. Often, you must think both backwards and forwards. Inversion forces you to uncover hidden beliefs about the problem that you are trying to solve.

Applying Munger’s thinking to my original point, it’s crucial to not only think about the best-case scenario for your investments. Considering the worst-case scenario compels you to carefully think about your portfolio, including:

1. Asset allocation.

Let’s say that you have a simple portfolio that’s invested 80% in equities and 20% in bonds. And consider a worst-case scenario where the stock market falls 50% from current levels and your equities do likewise. That means your investment portfolio would suffer an overall loss of 40% (a 50% drop in equities multiplied by 0.8, the proportion of your portfolio in stocks).

Before you say that type of fall in stocks can’t happen, know that developed markets have regularly dropped by that amount, and more, throughout their history.

How would you react to a portfolio drop like this? A lot of investors would sell equities after large losses and put that money into defensive assets such as cash and bonds. That’s often the worst thing to do, as assets such as equities aren’t usually down for long.

If you can’t stomach a fall such as this, then it’s time to reconsider your asset allocation. Perhaps you can reduce the 80% invested in equities and put more into bonds and cash. Or you can consider allocating a portion to assets that aren’t as correlated to equites, such as alternative assets.

Preparing for a worst-case scenario is a good way to stress-test the asset allocation in your investment portfolio.

2. Investment style/strategy

One of the biggest mistakes that I often see is investors don’t have portfolios that reflect their personalities and temperaments. For instance, you can have an investor with a conservative personality who has a portfolio 100% exposed to growth stocks.

Thinking through the worst-case scenario for your investments can help better match a portfolio with your personality.

Going back to our previous example, a conservative investor would normally struggle to handle a 40% fall in their portfolio, therefore it would make sense to dial back the equity exposure. Or if you’re a retiree who relies on the income from your portfolio, having a more yield-oriented asset mix would likely be a more palatable option.

3. Choosing stocks

Let’s move from asset allocation to choosing stocks, where looking at different scenarios is just as important.

On this point, it’s no accident that some of the world’s best investors started out as gamblers. For instance, Ed Thorp was an academic turned amateur gambler, who invented card counting and wrote a famous book about it (Beat the Dealer) when he was 30. Later, he applied his mathematical prowess to investing, running a successful hedge fund for 19 years.

Jeff Hass was a professional gambler before cofounding the Susquehanna International Group, which has turned into one of Wall Street’s most successful trading firms and made him the 48th richest person in the world.

Why do gamblers make good investors? It’s not only about the ability to take risk. It’s also about taking sensible risk, preferably where the odds are overwhelming in your favour. To do this requires scenario-based thinking, looking at both the best-case and worst-case scenarios, and everything in between.

Let’s look at an example of how this might work in practice. Woolworths (WOW) is the portfolios of many Australians. It’s a dominant supermarket retailer operating in an oligopolistic industry. There’s a lot to like with revenue growth that’s stable and secure, tracking closely to nominal economic growth. On the cost side, Woolworths has immense bargaining power with its suppliers due to its scale.

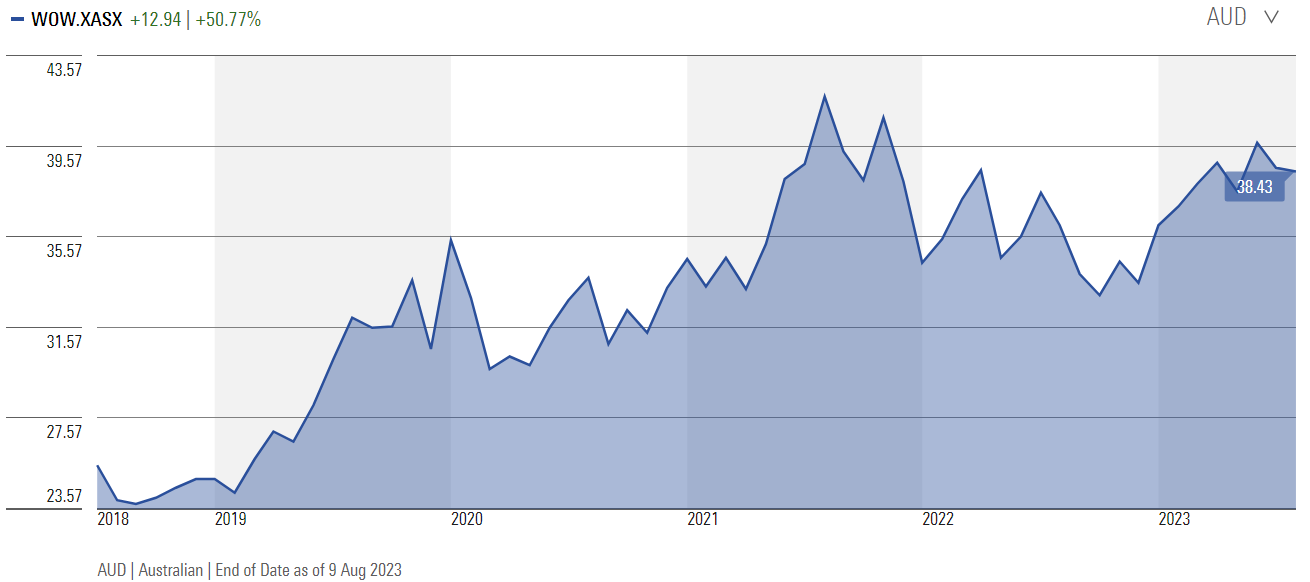

The stock has performed well of late as investors have turned to defensive stocks given their jitters about the economic outlook. Woolworths is trading on 27x forward earnings, well above the market’s 15x.

At a high level, you can look at the company’s revenue growth in future tracking around 5% as it has in the past. And if you assume stable to slightly increased margins as some of the current cost pressures ease, there might be earnings growth of high single digits in a best-case scenario. Combined with a stable earnings ratio of 27x, that would equate to around an 6-9% return in the long term.

And you can stress-test the earnings and multiple attached in all sorts of ways. In a worst-case scenario, you can look at an economic recession and how that could impact earnings. Maybe you forecast declining margins in this scenario and lighter revenue growth, resulting in earnings growth in the low-single digits.

The price-to-earnings ratio of Woolworths certainly needs testing. It’s trading at the upper end of its historical range. If it traded at 15x earnings as it did less than a decade ago, and you apply single-digit earnings, you can come up with a bear case scenario for the stock in 3, 5 or 10 years time.

To get sophisticated, you could apply odds to different scenarios occurring, and come up with your own price target for Woolworths.

Considering various scenarios, including the worst case, can help you have a better understanding of the key drivers for companies such as Woolworths and their prospects.

James Gruber is an assistant editor for Firstlinks and Morningstar.com.au