Sometimes, it pays to focus more on 'personal' than 'finance'

Personal finance is personal; or why you should focus on the value of non-monetary returns

The global pandemic brought with it a massive re-examination of personal priorities. The Great Resignation along with more people moving from cities to suburbs and smaller towns are just a couple of examples of how people seem to be changing how they value tradeoffs in their work, home, and financial lives.

Those case studies involve money, but money isn’t the only factor. People are choosing retirement or jobs that are more fulfilling or provide more balance. They are moving to locales that offer more space, natural beauty, or just quiet. Everywhere you look it seems people are increasingly focused on maximising their overall quality of life.

These trends illustrate something oft overlooked by financial professionals: that major financial decisions involve both monetary and non-monetary tradeoffs.

When Economics Gets Emotional

Let’s go back to Economics 101 for a moment and the foundational concept of utility. In finance, we think a lot about optimizing utility, but what is utility? Utility is a measure of value, but it isn’t simply dollars and cents. Utility is defined as the total satisfaction that can be derived from consuming a good or service.

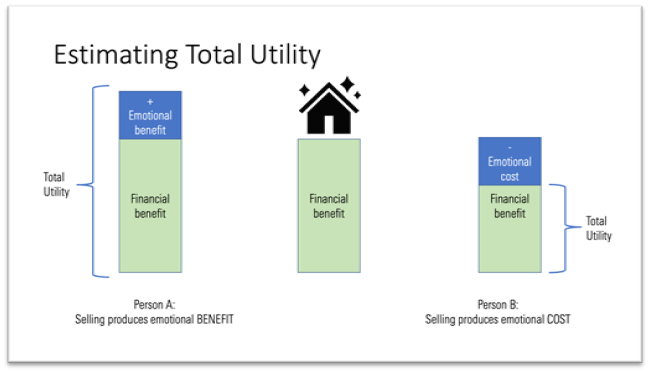

It’s tempting to take the mental shortcut of assuming more money = more satisfaction. After all, money is far simpler to measure than satisfaction. But maximising utility is not the same as maximising returns. Utility is subjective and comprises many factors. Ignoring emotional costs and benefits leads us to incorrectly evaluate the total utility of tradeoffs.

No Amount of Money is Worth THAT

When we evaluate tradeoffs, we perform mental cost-benefit analyses. Which option has the highest value when all is said and done? Which will give us the greatest total return on our initial investment? Some of the costs and benefits we consider are financial. Some are emotional. Some are psychological.

I was once offered a position at a large company that would have meant a significant increase in pay, but the job would have required much more travel and the work was not very interesting to me. I turned that offer down because, when I did the cost-benefit analysis, the emotional and psychological costs involved in the day-to-day work and the increased time away from my family outweighed the additional money.

I know I’m not alone in this, and I don’t consider this to be irrational or sub-optimal. I was not focusing on maximising my financial returns but on maximising total utility.

Many of us can think of actions so abhorrent that no amount of money could induce us to participate. When we evaluate the costs and benefits of the tradeoff, the psychological and emotional costs outweigh the financial benefits, and the overall utility of the tradeoff is not attractive. Likewise, some tradeoffs offer benefits above and beyond the financial.

Price /= Value

We've said it before. We'll say it again. Price is not the same as value. Price is what you pay for something, value is what you get. We equate these things at our peril.

Here, it’s important to note the prime directive of most people’s lives is not to maximise the market price of their assets. As complex beings, we have goals in life that go far beyond the realm of financial security and freedom. Yes, these things are important, worthy goals, but if financial advisers focus solely on maximising financial returns on investments, they miss the greater purpose of financial planning.

Personal finance isn’t about maximising the amount of dollars a person collects in their lifetime. It’s about making good choices with our limited resources so that we can live the lives we want to live. Dr. Brian Portnoy of Shaping Wealth puts it best, I think, when he says the true goal of financial planning is, "funded contentment."

I know some of the purists out there will argue that the purpose of financial management is to maximise the dollars and cents, so the client can use that money to create a life they want. More money means more ability to create that life, so maximising dollars and cents is the goal of the financial manager.

To these cynics, I would argue that many financial tradeoffs carry with them emotional costs and benefits that cannot be separated from the transaction.

In these instances, ignoring emotions causes us to value outcomes incorrectly. I know scores of people who would turn down even triple-digit returns if it required them to directly harm others or significantly deplete the planet of natural resources. To the purist who thinks only in terms of numbers, this is irrational, but to these decision-makers the tradeoff is clear and there is no sense of loss or missing out by not pursuing such actions.

More Than a Feeling

Consider, for example, a person who is thinking about selling their house after a painful divorce. The house is an asset with a specific financial value, and you can easily estimate the financial return that they can achieve through the sale. However, the emotions they associate with the house will affect the total utility of the transaction.

In this example, Person A associates the house with the negative emotional and psychological aspects of the broken relationship, and so selling the house and moving somewhere new would provide an additional benefit above the financial.

Person B associates the house with the family they’ve nurtured and the roots they’ve set down. It provides for them a much-needed sense of continuity and stability in an otherwise tumultuous and uncertain time. For Person B, to sell the house would exact an emotional cost, reducing the overall utility of the transaction.

Thinking about financial tradeoffs through the lens of maximising utility allows us to easily explain many human behaviors that don’t make sense through the lens of finance alone. It can also help explain how two people can have wildly different experiences of similar financial transactions.

Personal Finance is More Personal than Financial

Crises reveal, and COVID is no exception. This elongated period of uncertainty, stress, and isolation has motivated a major re-examination of priorities for many, and macro socio-economic trends suggest that people are giving more weight to the non-financial aspects of their work and home lives than before the pandemic.

These trends shine a spotlight on the non-financial aspects of financial tradeoffs, and wise financial professionals will take note. Thinking about financial tradeoffs in terms of maximising utility rather than dollars can help explain why numbers alone are not always convincing to clients.

Advisers who learn to incorporate the emotional and psychological aspects of decisions into their thinking will find that they are more equipped to work side-by-side with clients to craft strategies that maximize quality of life. Helping clients reach the ultimate goal of "funded contentment" is a valuable service indeed.