Market fall reveals your risk tolerance and loss aversion

You need to find the balance between risk tolerance and a good night's sleep.

"Each person has to play the game given his own marginal utility considerations and in a way that takes into account his own psychology. If losses are going to make you miserable—and some losses are inevitable—you might be wise to utilise very conservative patterns of investment and saving all your life. So you have to adapt your strategy to your own nature and your own talents. I don’t think there’s a one-size-fits-all investment strategy that I can give you.”

— Charlie Munger, 1998, answering, "How do you learn to be a great investor?"

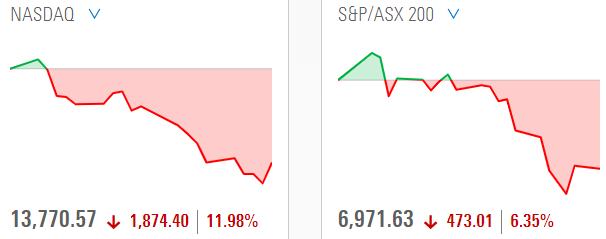

A week ago, the S&P/ASX200 entered what is known as a 'market correction' when it fell more than 10% from its recent peak in August 2021. Like the US S&P500 and NASDAQ, the index has recovered some ground in recent days, but here are the moves since the start of the year.

Experiencing a 10% fall is a good time to take stock of your risk tolerance. If you held $1 million in equities and the value fell $100,000, what did you think?

A) No big deal. That's the price of investing in shares and I'm focussed more on the long term, OR

B) $100,000!!! What I could do with $100,000! That's a year of hard slog to earn that much. There goes the mortgage repayment and new car.

Or maybe a worse reaction if you are in retirement and living on your savings. Retirement planning requires guesswork about the future, and 'losing' 10% might seem like a big hit when you are carefully drawing down 4% a year.

Are you someone who welcomes lower share prices as a buying opportunity, or loses sleep when the market falls? What if it goes down another 20%? Or 50%? If this seems unlikely, consider the following chart from Ashley Owen of Stanford Brown. Over 100 years, there have been 43 falls of over 10%, meaning equity investors should expect one every couple of years. And a 50% fall has happened every 25 or so years.

Data is All Ords Index, chart being updated to add 2020 fall.

There is no single and simple answer to how much market risk an investor should take. There is a difference between 'risk tolerance' and 'risk capacity' but we tend to interchange the two. Tolerance is an investor's comfort (or discomfort) with risk, whereas capacity is how much risk an investor can take without ruining their financial plans.

Tolerance for risk

Everyone has a different loss discomfort level and it varies over time and according to market conditions. While any number of risk appetite tests can be done in advance, nobody knows their tolerance until they face a real rather than imagined loss.

Some people genuinely look to an investment horizon decades into the future and have a strong ability to ignore market noise and fluctuations. They remain heavily exposed to equities for long-term growth and are sanguine about the potential for half their retirement savings to be wiped out.

But they are likely in the minority. For many, a $100,000 correction means doubt sets in, as it might be heading towards a loss of $200,000 or $300,000 which would compromise plans. In choosing to sell before it gets worse, another investor exits in a down market.

There is a common argument that younger people have greater risk tolerance, because they have more time to recover from a drawdown. But often the young person is saving over a shorter-term horizon than retirement, especially the deposit on a house, and a loss can be a setback toward the Great Australian Dream. Young people suffering a market loss may be discouraged from investing later in their lives.

Lack of capacity for losses in older people

Retirees may be hit by a market fall at the point when their retirement savings are at their maximum, the so-called ‘sequencing risk’. A loss of capital at a time of regular withdrawals may reduce the estimated period until the money runs out.

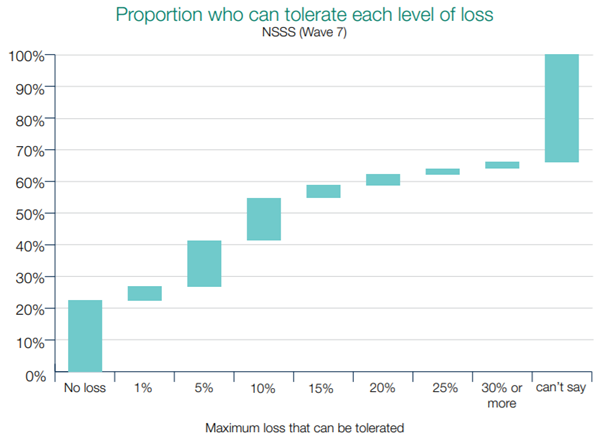

National Seniors Australia released a survey of nearly 5,000 of its members in 2018 which showed little capacity to tolerate losses in retirement savings. About 23% reported they could not accept any annual loss on their portfolio, as shown below. Most respondents could not tolerate losses of over 10%, and only one in 14 a loss of 20% or higher (note in the table that the large box on the right is ‘can’t say’). National Seniors reported:

“Of those who could quantify their risk tolerance, only 11% could tolerate a loss equal to the impact of the GFC. Those who admitted in the survey to not knowing how to manage their market risk are twice as likely to report ‘no tolerance for any loss’ as those who said they could manage it.”

The theory of loss aversion under challenge

We’re all different but if there was one widely-accepted behavioural trait, it was that most people are influenced by ‘loss aversion’. Loss aversion is a notion that we dislike losses far more than we enjoy equivalent gains. Daniel Kahneman, the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economics winner, in his bestselling book, Thinking Fast and Slow, went as far as saying:

“…the concept of loss aversion is certainly the most significant contribution of psychology to behavioral economics.”

His colleague, Richard Thaler, was awarded the 2017 Nobel Prize in Economics, and ‘loss aversion’ featured 24 times in the Nobel Committee’s description of his contributions to economics.

It seems to reflect a fundamental truth. Dozens of academic studies have attempted to quantify loss aversion, and Kahneman says:

“You can measure the extent of your aversion to losses by asking a question: What is the smallest gain that I need to balance an equal chance to lose $100? For many people the answer is about $200, twice as much as the loss. The ‘loss aversion ratio’ has been estimated by several experiments and is usually in the range of 1.5 to 2.5.”

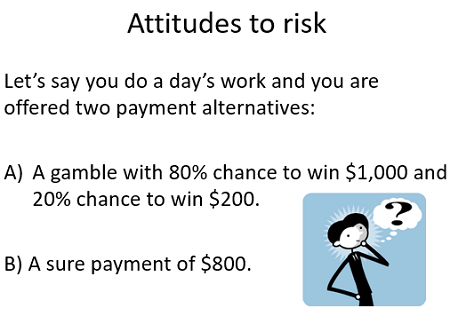

It doesn’t seem logical, but for many years, I have used the following slide to reveal how loss averse people are. Say someone does a day’s work, and is offered two payment alternatives, as shown. The expected value of A) is $840 (80% X $1,000 plus 20% X $200) and B) is $800, yet nearly everyone chooses B). In fact, when I change the slide to lower B) to $600, most people still want the certain payment rather than the gamble.

However, now there is a body of work saying loss aversion is a fallacy, that there is no general cognitive bias that leads people to avoid losses more vigorously than to pursue gains. For example, David Gal, Professor of Marketing at the University of Illinois at Chicago, writing in Scientific American, says:

“People do not rate the pain of losing $10 to be more intense than the pleasure of gaining $10. People do not report their favorite sports team losing a game will be more impactful than their favorite sports team winning a game … To be sure it is true that big financial losses can be more impactful than big financial gains, but this is not a cognitive bias that requires a loss aversion explanation, but perfectly rational behavior. If losing $10,000 means giving up the roof over your head whereas gaining $10,000 means going on an extra vacation, it is perfectly rational to be more concerned with the loss than the gain."

Yet Kahneman’s statement that ‘losses loom larger than gains’ has much support and to me, feels right, based on my personal experience with investing. I don’t enjoy gains anywhere as much as I dislike losses, and it influences my investing. I have long accepted the estimate that loss aversion:

”…is a cognitive bias that describes why, for individuals, the pain of losing is psychologically twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining.”

But even Kahneman now says loss aversion was not so much the result of rigorous experiments as an intuition. When David Gal reproduced a typical Kahneman study about how much students would sell their mugs for, he found his subjects were largely indifferent. The desire to buy or sell at certain prices was met more with inertia than a feeling of gains or losses. Other researchers have expressed similar concerns, arguing that we are not hard-wired to give negative results such significant weights. So Gal calls loss aversion theories ‘fuzzy and loose’, when often actions can be explained by other factors such as the endowment effect or a bias towards inaction.

Asked to react to Gal’s work, Kahneman, now aged 87, said:

“It’s not a law of human nature that you have to find it in every context ... There are experiments where people don’t find loss aversion. And, again, there’s an explanation for every one of them. That doesn’t violate loss aversion, because there are exceptions to loss aversion ... Having a principle that helps understand a wide body of phenomena—that’s considered useful. That doesn’t mean that loss aversion’s true. It means that it’s useful.”

Find your own risk tipping point

As Munger said: "If losses are going to make you miserable—and some losses are inevitable—you might be wise to utilise very conservative patterns of investment and saving all your life."

But an investor with a highly-conservative, long-term portfolio will forgo substantial returns over multiple decades, and the opportunity cost might deliver as much angst as a short-term market loss. It would feel like everyone else is drinking punch and dancing at the party while you're lying at home in your bed.

The best strategy is to find that point where there is enough equity market exposure to enjoy the gains, but not too much that losses cause great worry. If being a little conservative is what it takes to get a good eight hours, it might be worth the cost.