Why investors should care about the banking scare

Banking crises are never just about the banks.

Almost 15 years to the day after investment bank Bear Stearns & Co. collapsed under the weight of bad mortgage bets that marked the beginning of the biggest financial firestorm since the Great Depression and led to widespread failures, massive industry reforms, and a long-lasting recession, the United States finds itself faced with yet another banking crisis.

It’s easy for investors to dismiss the ripples from the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank as contained and nothing to worry about when it comes to a broader portfolio.

But if there’s one thing to know about banking crises, it’s that they are never just about the banks. They may start there, but they don’t end there. Easy financial conditions tend to lead to higher risk-taking and a complacency that long-established patterns will continue. Until they don’t.

As Warren Buffett has been known to observe, only when the tide goes out do you see who’s been swimming naked.

The worry is fear

The failure of two major regional banks since Friday threatens to erode investor and consumer confidence to a degree that could spiral in unexpected ways. And with inflation still raging at the highest levels in 40 years and the Federal Reserve raising interest rates at the most accelerated pace since those years, things are starting to break.

“The worry is about fear,” says Tim Murray, capital markets strategist for multi-asset portfolios at investment manager T. Rowe Price.

In good times, too, policymakers get lax and tend to feel like it is safe to repeal or reduce important protections designed to prevent systemic events and consumer safeguards.

Cases in point: The repeal in 1999 of the Glass-Steagall Act—enacted in response to the Great Depression and which separated commercial banking and investment banking activities—was widely seen as a factor in the 2008 financial meltdown and led to the notion of large banks being “too big to fail.” More recently, the easing in 2018 of regulatory oversight over small and regional banks is seen as a contributor to the current crisis.

T. Rowe’s Murray notes that a difference between the last crisis and this one was the speed with which federal regulators acted to stem the problem this time around. “It looks like the Fed quelled the immediate risk,” he says.

But risks remain.

Recession risks are elevated

For investors, it’s a critical time to watch for spillover effects from the banking crisis that could feed through to the broader economy.

There’s heightened uncertainty that more shocks could be lurking, especially given the backdrop of the Federal Reserve’s aggressive rate hikes of the past year and the concern that other investment business models based on lower interest-rate assumptions could emerge.

Just last September, the Bank of England was forced to rescue pension funds after a series of interest-rate hikes exposed weaknesses in so-called “liability-driven” investments. There was talk then that we were seeing the first tremors of a potential financial crisis.

“This increases the chance of a recession,” says Murray of T. Rowe Price. He suggests that banks will become even more risk-averse in making loans than they had already been leading up to this. “That will create more of a headwind for the economy, and the economy is already fragile.”

The Fed is in a bind as it seeks to calm markets while at the same time fighting inflation without causing a sharp slowdown.

Just a week ago, Fed Chair Jerome Powell told the Senate Banking Committee that the central bank was considering raising the benchmark federal-funds rate by a half-percentage point when it meets next week and would likely boost rates to a higher extent than previously expected based on sticky high inflation and continued strength in the labor markets.

Now, traders surveyed by the CME Group for its CME FedWatch Tool have taken that 0.50% move off the table at the March meeting. About 68% see a 0.25% move, and 32% predict the Fed will pause.

In a bulletin to investors Monday, BlackRock said the shuttering of the banks and the emergency measures taken by regulators likely “prevented wider contagion” but added that the events reinforced its “expectation of recession.”

Yet, BlackRock, the largest investment management company in the U.S. with $8.6 trillion under management at year-end 2022, expects the Fed to carry on with its “rate-hike campaign,” explaining that by “shoring up the banking system, the Fed can focus monetary policy on bringing inflation down to its 2% target.”

A combination of rising rates and risk aversion quickly conjures up two words: credit crunch.

“We see financial conditions and credit supply tightening, especially to sectors such as tech,” BlackRock wrote in its bulletin. “These developments are also likely to hurt confidence and increase risk aversion.”

What went wrong at SVB and signature bank?

US federal regulators seized SVB Financial on Friday and Signature Bank on Sunday.

Both banks were big lenders to early-stage startup technology companies and their founders, with Signature focused on the nascent and controversial cryptocurrency industry.

Both banks’ deposit bases were heavily concentrated—90% or more—in accounts exceeding the FDIC-insured limit of $250,000. Retail deposits typically are more stable and considered to be safer as they usually fall well within the range backed by the government.

SVB, in particular, was heavily exposed to outsize unrealized losses. Its deposit base grew from $49 billion at year-end 2018 to more than $189 billion by year-end 2021, tracking the huge wave in venture capital funding that was at all-time highs during that time frame. Many of its clients held business and personal accounts at the bank. Morningstar analysts calculate that SVB’s deposit base increased 57% a year between 2018 and 2021 compared with industry deposit growth of 12% a year.

As deposits swelled, the bank directed the money into longer-dated Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities. When the Fed began boosting interest rates a year ago, the value of those securities fell, and SVB was sitting on substantial unrealized losses. At the same time, the boom times in venture capital went bust as high-flying startups fell out of favor and the IPO market came to a standstill. SVB’s main source of deposits dried up. Clients started yanking money in quest of higher yields and as their businesses burned through cash.

SVB announced Wednesday afternoon that it sold its $21 billion bond portfolio at an aftertax loss of $1.8 billion and was seeking to shore up capital. In a call with certain customers, the chief executive urged calm. Instead, many of them took to their social media soapboxes and urged other customers to get out. There are no friends on Wall Street, right? SVB’s bid to raise capital failed. Regulators swiftly intervened.

Signature’s ties to cryptocurrency may have sealed its fate, especially after struggling crypto-focused Silvergate Bank earlier last week said it was shutting down and returning deposits.

SVB and Signature represent the second- and third-largest bank failures in U.S. history after the 2008 collapse of Washington Mutual.

Regulators assured that all depositors, even those above the insured limit of $250,000, would be made whole. Moreover, a new emergency funding facility called the Bank Term Funding Program will provide loans to banks, credit unions, and savings associations for up to one year in exchange for Treasuries to ease any strains and prevent systemic risk.

In a sign of how times change, Barney Frank, the former Democratic congressman from Massachusetts who was one of the principal architects of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 that led to sweeping financial regulatory reforms and safeguards in the wake of the Great Recession, retired in 2012 and joined the board of Signature Bank in 2015. He became a vocal proponent of a bill to roll back regulatory oversight for banks with under $250 billion in assets that passed under the Trump administration in 2018.

Credit Suisse added to jitters about the health of the overall financial system when it revealed that if found “material weaknesses” in its financial reporting the past two years because of lapsed internal controls. Nonetheless, the troubled investment bank maintained that its financial statements “fairly present, in all material respects, the group’s consolidated financial position.”

Flight to Safety in Bonds

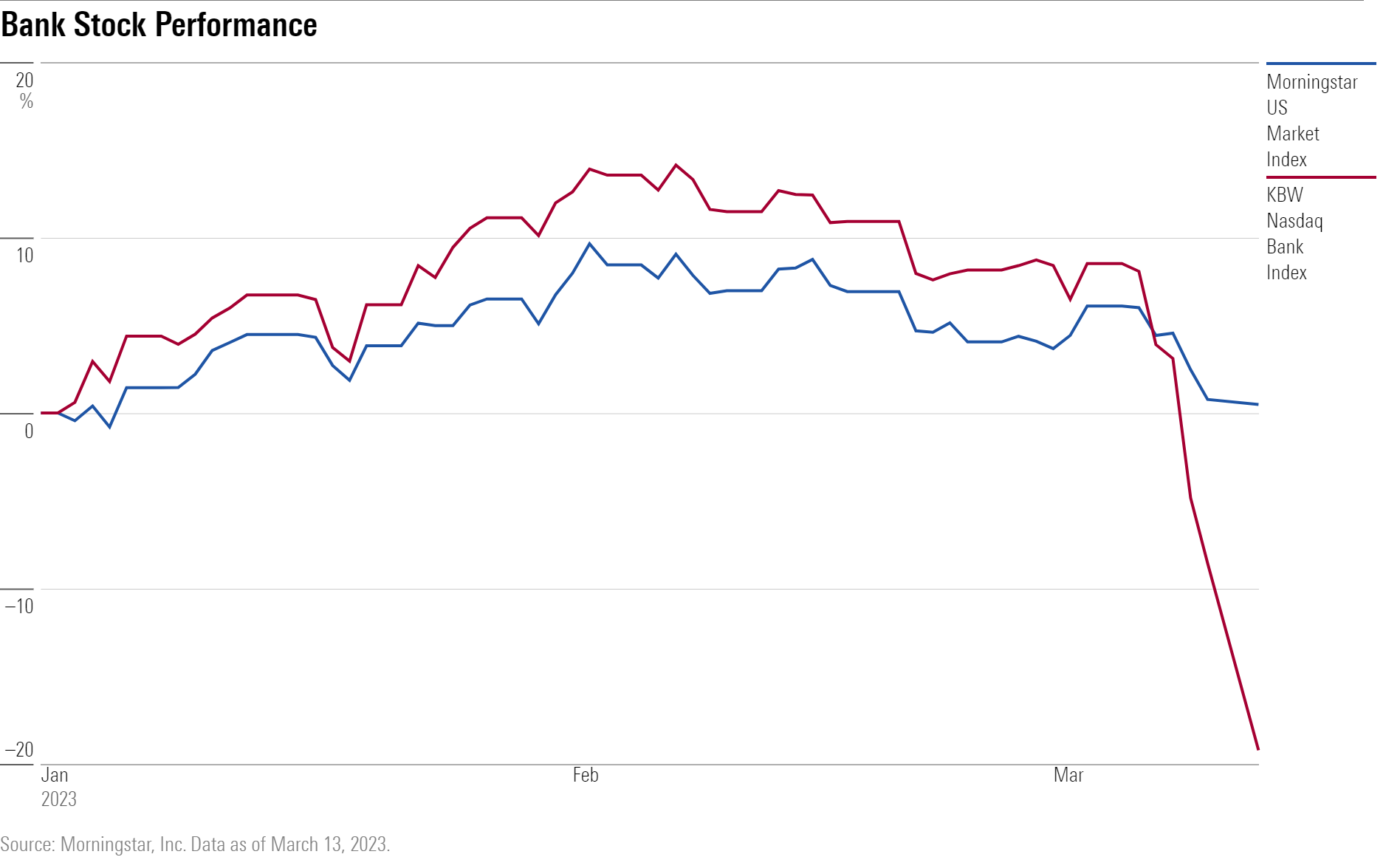

The banking scare has played out primarily among bank stocks and in the bond market.

US bank stocks have taken a big hit, with the KBW Nasdaq Bank Index falling 22.1% in just three days.

Banks broadly are seen by investors as being less attractive given that their cost of funds is destined to rise. They are also now on the hook for any shortfalls to the government insurance fund as a result of protecting uninsured deposits, and regulatory oversight of regional banks could be amped up again.

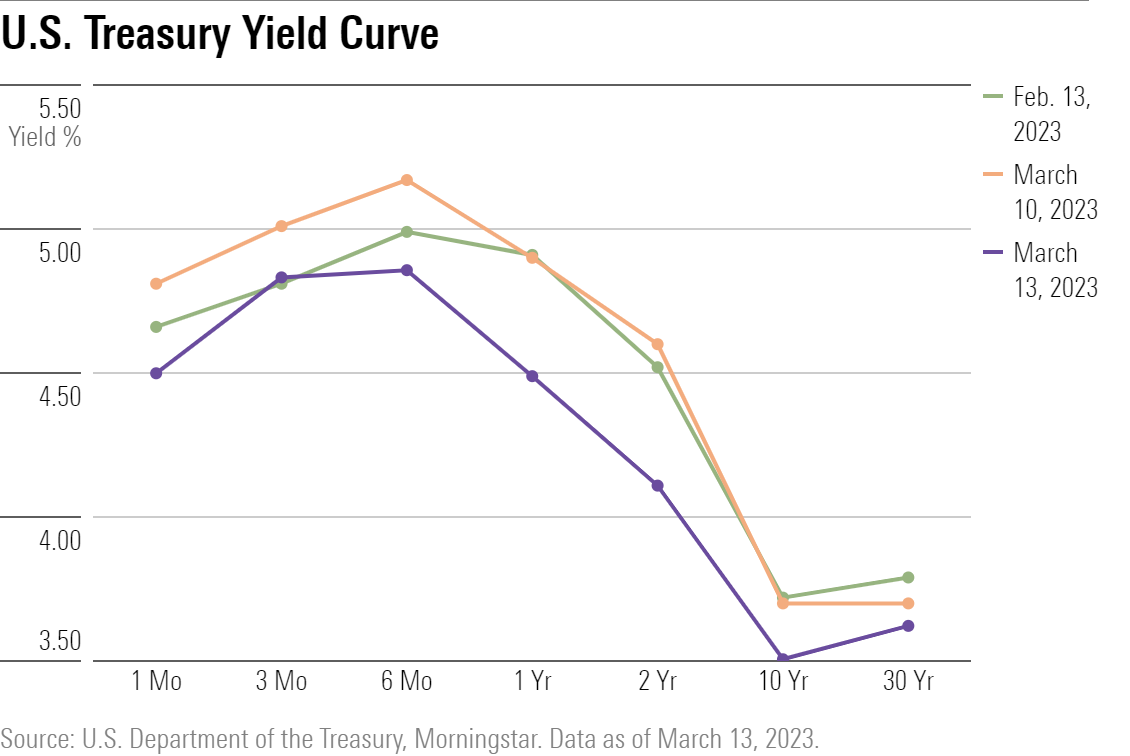

Perhaps more notable is the shift in the US Treasuries market since the crisis at Silicon Valley Bank came to a head last week. Up until the emergence of the banking scare, bond yields had been back on an upswing as investors felt the Fed would need to take interest rates even higher than had been expected and keep them high for longer.

However, sentiment has shifted dramatically, with investors now believing that while the Fed will raise interest rates one or two more times before June, the central bank will be cutting interest rates as soon as the third quarter amid ripples from a potential credit crunch.

Two-year Treasury yields marked their biggest three-day drop since October 1987, falling to 4.0% as of Monday night from 5.1% at the close of trading last Wednesday.

Investors are finding out that naked swimmers at low tide are very rarely a pretty sight.