Who is winning from rising inflation? Firstlinks Newsletter

Rate rise winners and losers; 5 lessons for bears; Asia interview; 3 investing themes; The value club; Dividend data; Scenarios; Jobs Summit.

While all the media attention focusses on the disquiet of borrowers facing rising interest rates, we overlook the investors who are enjoying a higher income flow on bonds and deposits. It is clear that a saver who earns 1% when inflation is 6% is going backwards by 5% in real terms. As interest rates rise, the same saver who now earns 4% will feel like their income has received a boost as it is covering more of the inflation impact. The pendulum seems to be swinging back to savers as interest rates rise.

But are the borrowers or savers winning from rising inflation and its impact on rates? It's commonly argued that governments can 'inflate away the debt' because they repay their maturing bonds with money that is worth less in future than when they borrowed it. In effect, the debt requires a smaller amount of the government's revenue as inflation eats away at the value of the borrowing.

So far so good. But does the same apply for households?

Last week, a friend asked whether, as a borrower with a large mortgage, he should be happy to see high inflation. That is, does inflation 'inflate away his debt'? In theory, if wages increase in line with the CPI, he still owes the same amount of money but he earns more. My first instinct was to follow the traditional reasoning that high inflation benefits borrowers.

But here's the catch. He said that rising inflation is leading to higher interest rates on his mortgage, but his salary is not increasing to match CPI. So how can his debt be ‘inflated away’ when it is costing him more and he does not earn the salary to match it. In what sense is his debt becoming less? How can someone with a large debt be pleased by high inflation when all he sees is mortgage pain?

Good question. How have governments 'inflated away their debt' in the past but the same logic does not apply now for households? I put this question to Shane Oliver of AMP as my head was starting to spin. He replied:

"Governments did inflate their way out of high debts left over from the end of World War 2 because post-war inflation combined with strong economic growth helped reduce the value of their debts relative to GDP. But that was a period of low bond yields. If bond yields had risen more in line with inflation, then governments would have found it a lot tougher.

It's harder for individuals. High inflation can help reduce a person's mortgage debt burden if interest rates stay low and wages growth is strong. This happened in the early part of the inflation surge in the first half of the 1970s when wages growth was well above inflation (in 1974 inflation rose to nearly 18% but wages growth was 25% or so) and interest rates were slow to move up with inflation. And back then, mortgage debt was relatively low (compared to people’s wages anyway). My parents benefitted in that period.

But right now we have the worst possible combination of high mortgage debt levels, rapidly rising interest rates and wages growth running well below the rate of inflation. Wages are nowhere near making up for the rise in interest payments on mortgages. So while the real value of the debt may be falling in the sense that consumer prices are rising faster than the value of the debt, it's not helping people with a mortgage due to slow wages growth.

So I don’t think the old concept of 'inflating the debt away' applies now to those with a mortgage."

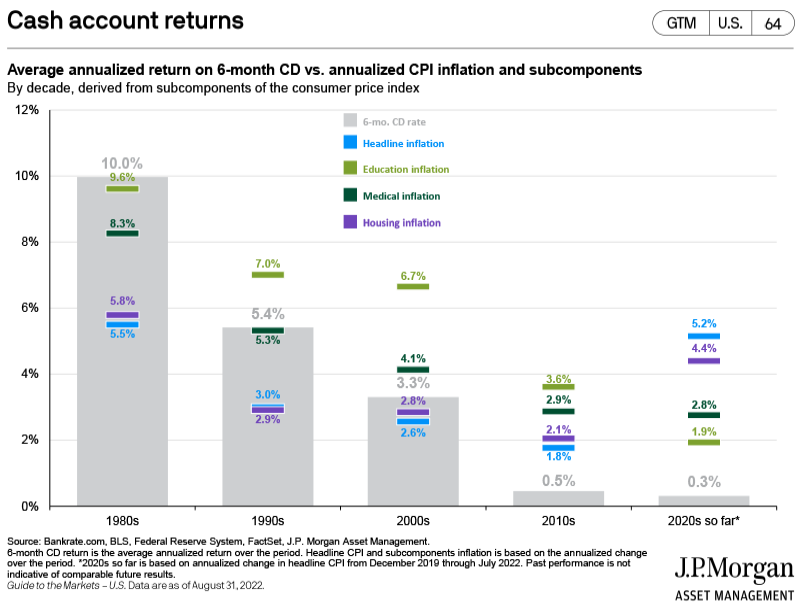

What about savers in the current inflationary environment, and what is the comparison with the past? A recent chart produced for the US by JP Morgan is a guide, as reproduced below. In the 1980s, high inflation pushed the Fed to increase rates rapidly, and the chart shows savers earned higher interest rates (the grey bars) than the level of inflation. In the 1990s and even 2000s, deposit rates generally kept up with inflation.

But gradually, as bond rates fell after the GFC, the inflation rate exceeded bond yields. That was the position in both the US and Australia in the 2010s and into 2020 as Covid hit. Bond and bank deposit yields fell to close to zero. Real savings yields were negative as inflation exceeded savings rates.

Over the last four decades, therefore, we have experienced high inflation with high rates, low rates with low inflation, and now we have low but rising rates with high inflation.

So which is best for households? For savers, it feels better to earn higher rates even if inflation is high. Retirees complained about 1% rates when inflation was 2% and probably prefer 4% rates when inflation is 6%. And borrowers are unhappy with rates at 4% when inflation is high rather than 2% when inflation is low, because wages are not growing to 'inflate their debt away'.

In the current inflationary conditions, it is the savers who feel better off than the mortgage holders.

On Tuesday this week, the Reserve Bank signalled more pain for borrowers:

"The Board expects to increase interest rates further over the months ahead, but it is not on a pre-set path ... The Board is committed to doing what is necessary to ensure that inflation in Australia returns to target over time."

At 1pm this afternoon (Thursday), the Governor of the Reserve Bank, Philip Lowe, will give an address to the Anika Foundation on Inflation and the Monetary Policy Framework. Every time he speaks, the media dissects each word for a hint on future policy. The fact that such depth of analysis has been misleading in the past does not reduce the enthusiasm.

We have now experienced five consecutive months of rate increases: four of 0.5% and one of 0.25%. Each time, the news programmes trot out the usual stories of young couples with large mortgages who will need to buy frozen vegetables instead of fresh. They could run the same stories from months ago.

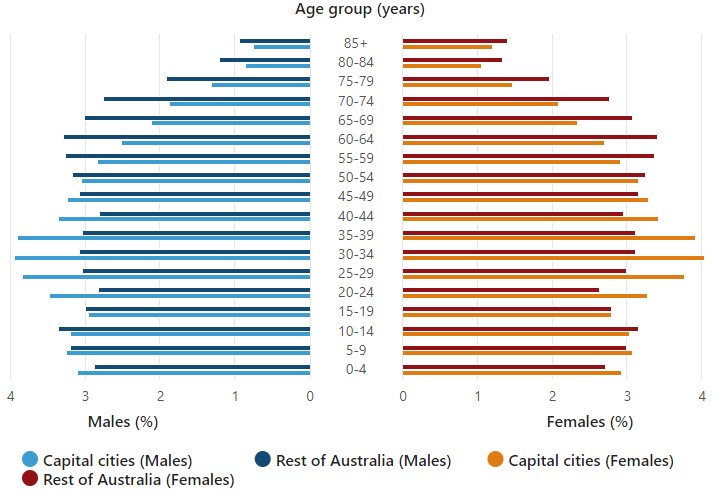

Who are the lenders and the borrowers, the winners and the losers? According to the ABS, the median age in Australia is 38.4 years, and:

- People aged 20 to 44 years made up 37% of the combined capital city population, compared with 30% of the population in the rest of Australia.

- People aged 55 years and over made up a smaller proportion of the population in capital cities (26%) than in the rest of Australia (34%).

Almost 80% of SMSF members are over 50 and their balances are far higher than for those under 50. About 75% of retirees own their home, and the desire of younger Australians to enjoy the Great Australian Dream shows little sign of abating. It's safe to generalise that younger people are the borrowers (or aspiring borrowers) and older people are the savers. Higher interest rates affect people differently depending on their resources, life stage and age, and we know from the Intergenerational Report that this chart will grow increasingly fat at the top (for example, 5% of Australians are expected to be over 85 by 2050).

Australian population by age and sex

The youngest members of the so-called Silent Generation (although many are far from silent) are 77, and with post-war frugality and home ownership, most are in the 80-100 years bracket where health, volunteering and estate management gain higher priority. Baby Boomers are currently aged between 58 and 76 and retiring in their thousands every week, and some are expecting to live another 30 years and prefer to live off income rather than capital. Home loans are either small or paid off.

We often overlook that the oldest of the Millennials - those young upstarts - are in their 40s, but many have large mortgages. This is the generation facing the major impact of rate rises on loans. They are the couples aged 26 to 41 that we see on the news when rates rise. And some of the freedom-loving, resourceful and independent Gen Xers can now retire, but many have mortgages, so there is a mix of fortunes in there.

One argument for the Reserve Bank continuing to increase rates is that levels of consumer confidence and spending remain high, and unemployment is at historical lows. In fact, Ross Gittins from The Sydney Morning Herald believes a tipping point has been reached where long-term unemployed have returned to the workforce and Australia will have a permanently lower unemployment rate. He wrote:

"By getting 125,000 long-term unemployed back into the working world, it’s lowered the floor under the unemployment rate by about 1 percentage point. So even if the economy turns down in coming months or years, the unemployment peak, however high, is likely to be about 1 percentage point lower than it otherwise would have been. It gets us closer to a level of full employment that makes more sense to an ordinary person who thinks full employment surely must mean unemployment close to zero."

Longer term, we need to challenge our assumptions of a return to low inflation in 2023 after a year of pain. Although the Reserve Bank still believes ...

"Inflation is expected to peak later this year and then decline back towards the 2–3% range. The expected moderation in inflation reflects the ongoing resolution of global supply-side problems, recent declines in some commodity prices and the impact of rising interest rates."

... there's another view, as Bernard Keane wrote in Crikey this week:

"Life is going to get a lot tougher for central bankers as climate change, worker shortages, pandemics, geopolitical instability and the growing use of sanctions create constant inflationary pressures on economies."

In this week's edition ...

Lisa Thompson and four of her colleagues from Capital Group draw on the lessons from a combined 171 years in the market, through bulls and bears, to highlight key takeaways on lessons learnt.

Our interview this week is with Andrew Swan from the Man Group, who is also a multi-decade investor now specialising in Asian equities. Most Australians are underweight Asian stocks but there are growing opportunities when developed economies are facing economic and demographic headwinds.

At the conclusion of the reporting season, it's more important to identify emerging themes than the short-term results from a few companies. Daniel Moore and Michael O'Neill from Investors Mutual identify three major trends all investors should know.

Steve Johnson of Forager has always been known as a value manager, looking for unloved stocks trading at an estimate of a discount to fair value. So now that one-third of his portfolio is in growth, has he changed his style?

Charlie Jamieson invests in the top end of the bond market in government securities, where finally after years of low rates, some value has appeared. He checks the prospects using scenario analysis with variations around his base case.

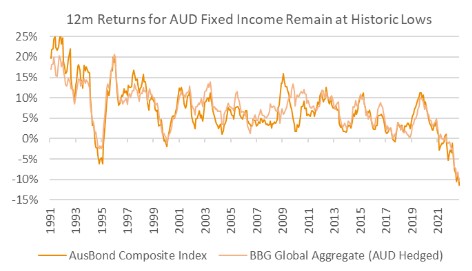

It's certainly been a wild ride in bonds with the AusBond Composite index down another -2.5% in August, taking the drawdown above 12%. It's even worse for some global investors, with the hedged Bloomberg Global Aggregate Index down 11% since its peak on 4 January 2021, but the unhedged index has lost around 20%. For any investor thinking that the time to buy in a market is after a selloff, it's worth checking bonds.

Regular readers will be familiar with Peter Thornhill's views on dividends from industrial companies, so how does he react to the massive payouts from resource stocks? He checks the numbers.

And the CEO of the Grattan Institute, Danielle Wood, received much acclaim last week at the Jobs and Skills Summit for her opening keynote address and how she set the tone for the event. We publish one of the section highlights plus links to the entire talk as a good summary of the issues facing Australia.

Finally, as we head into spring and summer, spare a thought for the Europeans about to face a winter with soaring electricity and gas prices. It will become a massive social problem. The Irish Times quoted a cafe owner hit by an electricity bill up 250% in a year to €9,836.92 for 73 days. That is a lot of cappuccinos.

Our White Paper this week is from Neuberger Berman, with a fascinating perspective on the development and rapid growth of private markets. Much in the news recently as Australian super funds increasingly rely on unlisted investments, it's also attracting far more retail interest.

For those who read Firstlinks and then don't return for another week, there are often fascinating comments on our articles. No exception are the 60 or so comments on That Horse Has Bolted and they're worth another look.