Manager profile: A growth fund without tech stocks?

Highly unorthodox moves that worked for this highly regarded manager.

Mentioned: Shell PLC (SHEL), British American Tobacco PLC (BTI), Enbridge Inc (ENB), Meta Platforms Inc (META), Fidelity Magellan (FMAGX), Alphabet Inc (GOOG), GQG Partners Emerging Markets EquityInst (GQGIX), Goldman Sachs GQG Ptnrs Intl Opps Instl (GSIMX), Virtus Vontobel Foreign Opportunities A (), Netflix Inc (NFLX), Philip Morris International Inc (PM), Shell PLC (SHEL), Schlumberger Ltd (SLB), Exxon Mobil Corp (XOM)

Peter Lynch, legendary manager of Fidelity Magellan (FMAGX) in the 1980s, was grateful for his fund’s name. He said that moniker—invoking a global explorer but skirting investment-related specifics—freed him to invest any way he wanted. He felt unconstrained by geography, market cap, or style.

Few equity managers today enjoy that level of freedom. One who comes close is Rajiv Jain, manager of Goldman Sachs GQG Partners International Opportunities (GSIMX).

In the past two years he has twice dramatically transformed his portfolio. These unusual actions deserve attention because such bold moves are quite rare and challenge some widely held investing maxims. And in the short term, they worked.

Buy and Hold, Until You Don’t

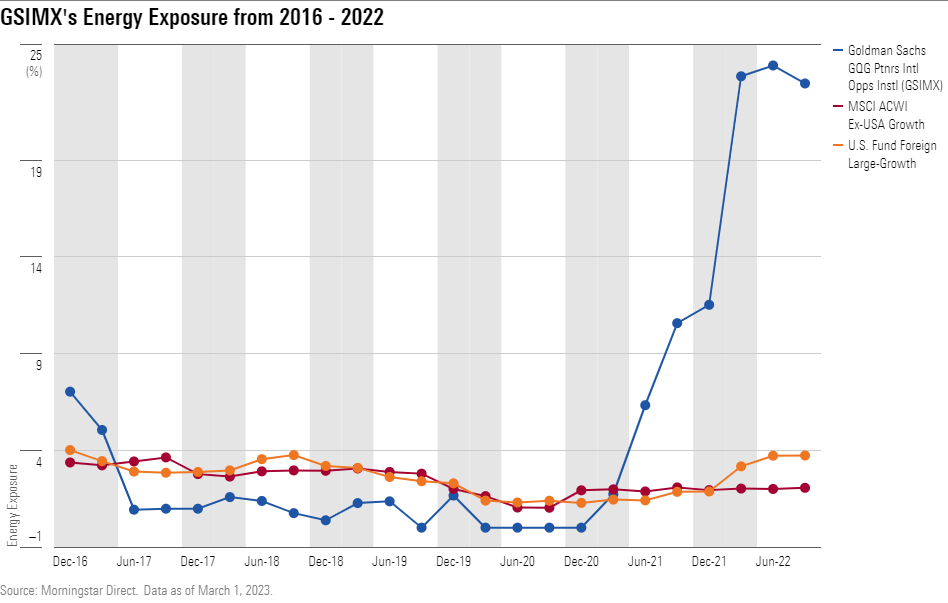

Energy stocks typically haven’t interested Jain. At the end of March 2021, GQG’s main international fund, Goldman Sachs GQG Partners International Opportunities, had almost no energy exposure—just 1.5% of assets, according to GQG. That wasn’t surprising, given the fund’s long-held growth tilt.

But things were about to change. Jain added energy stocks throughout 2021; in the third quarter alone, for example, he bought ExxonMobil (XOM) and increased the fund’s stake in Petrobras. In the following quarters Jain added Shell (SHEL), Enbridge (ENB), and Schlumberger (SLB). By the end of December 2022, the energy stake had soared to 24.2%. (Separately, the fund’s consumer staples stake nearly tripled, to 23.1% from 8.4%.)

The fund didn’t hold much cash, so the money to buy energy and staples stocks had to come from somewhere. Technology stocks took the biggest hit. The fund’s IT stake plunged to 2.7% from 20.9% from March 2021 to December 2022. Consumer discretionary also fell, to 1.6% from 11.1%.

As a result, the fund’s portfolio moved all the way to large-value from large-growth in the Morningstar Style Box before edging back to the border between large-value and large-blend.

Steering away from two of 2022′s weakest sectors into two of the strongest had a powerful impact. Although the fund’s I shares still lost 11.1% in 2022, they ranked at the very top of the foreign large-growth Morningstar Category.

Such rapid and decisive shifts are rare, usually occurring when a new manager with a much different investment philosophy takes over a fund. That they happened at a fund with a veteran manager and well-established approach raises many questions. Did Jain diverge from his typical investment approach, or has he made similar moves in the past? After such a drastic change, should Goldman Sachs GQG Partners International Opportunities still be considered a growth fund? Is such a sudden, audacious move a tactic other managers should adopt? Finally, what should we expect from here?

Been Here Before

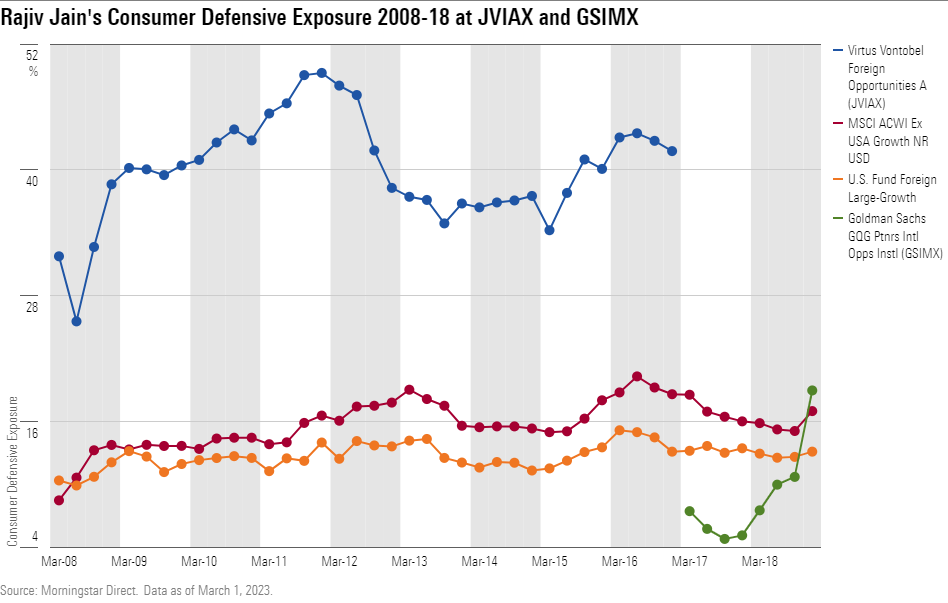

Jain cofounded GQG Partners in 2016 after a long and successful tenure at Vontobel, where he ran a broad international fund, an emerging-markets fund, and a global fund. During that time, Jain was known for unusual sector weights, including huge overweightings in consumer staples and India. He kept those bets in place for years.

The first portfolios at GQG, though, differed radically from the ones he’d left behind. Most noteworthy was the dramatic fall in his former favorite sector. The first publicly released portfolio from GQG’s international fund, from the end of 2016, had less than 10% of assets in consumer defensive stocks according to Morningstar data. That’s a far cry from the roughly 40% his last Vontobel Foreign Opportunities (JVIAX) portfolio had contained nine months earlier.

Jain offered a straightforward explanation. He told Morningstar that the slowing growth and higher valuations of many consumer-products firms had rendered them unappealing. In particular, the tobacco firms he’d long favored for their steady growth faced challenges from e-cigarettes. GQG’s international fund outperformed the category average over the following three years.

Therefore, Jain’s 2021-22 move into energy and consumer staples and away from tech and consumer cyclicals was not the first time he’s made a rapid and drastic shift. What’s more, Jain didn’t leave consumer-defensive stocks behind forever. Taking gradual steps, he returned to that territory, including tobacco stocks, in subsequent years. Consumer defensive stocks recently were more than 20% of the GQG international fund’s assets, less than half the Vontobel fund’s peak but roughly double the category average. British American Tobacco (BTI) was the GQG international fund’s number-two holding at 6% of assets as of its December 2022 portfolio, with Philip Morris International (PM) at number six with 3.1%, because Jain thinks the threat from e-cigarettes has faded.

Jain thinks conditions for companies, industries, and countries change rapidly these days, and only an overly rigid investor would fail to adapt. If that means overhauling the portfolio quickly, so be it.

A Russia Reversal

Interestingly, Jain pulled off an even more rapid reversal in early 2022. GQG Partners Emerging Markets Equity (GQGIX) entered that year with 16% of assets in Russian stocks, the most of any fund in the diversified emerging-markets category. As the signs of Russia’s intentions regarding Ukraine grew more and more ominous, Jain decided to act. In January he started selling his Russian stocks. By the time the invasion began, the fund’s exposure was down to 3.7%.

That smaller stake still roughly matched Russia’s weight in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index and dented the fund’s returns when, shortly after the invasion, the remaining stocks had to be valued at zero. But the fund would have been much worse off had Jain not drastically reduced the position in such a substantial and timely manner.

Russian stocks were falling even before the Feb. 24 invasion, but judging from his comments and his fund’s results, it appears that Jain sold much of his Russian position before the steepest declines.

He did not claim to have foreseen actual warfare—in fact, he said afterward that he had assumed Russia would not invade because it would be so irrational to do so. But he still acted more decisively than other managers with meaningful Russia exposure. Jain’s about-face on Russia offers another demonstration of his willingness to ignore the widely held notion that a successful investor must always have a long time horizon and a low turnover rate.

Jain did have low turnover in the past. In the five years through 2014, the annual turnover rate at his Vontobel international fund exceeded 35% only once. In the past three years at GQG, the international fund’s turnover rate has ranged from 72% to 137%. When questioned in April 2022 about the sharp rise in the fund’s turnover rate, Jain told Morningstar that conditions had changed decisively, and he felt it appropriate, even necessary, to adapt. In particular, the arrival of the global coronavirus pandemic in 2020 created vastly different prospects for some firms. Later, he said Big Tech firms’ declining growth rates combined with the improving fundamentals for energy firms amounted to a regime change.

What Happened to That Growth Tilt?

Jain named his firm GQG to stand for global quality growth. He considers himself a quality growth investor. His funds at Vontobel and GQG almost always landed in the large-growth portion of the style box. But Jain, who pays close attention to both U.S. and non-U.S. stocks, doesn’t think any company or sector merits the growth label permanently. Why should Netflix (NFLX), he asks rhetorically, be considered a growth stock when its subscriber base growth slows or reverses?

By contrast, he said energy firms attracted his attention because they showed better current financials and growth metrics, offered more attractive growth potential, and were available at reasonable prices. In other words, he contends, he hasn’t abandoned his growth standards to own energy stocks. Energy stocks started meeting his growth and valuation criteria, allowing him to own them.

Most other managers hesitate to accept energy firms as growth stocks, and they barely register in the growth benchmarks of index providers such as Russell and MSCI. But at least one prominent index provider does agree with Jain that some tech firms have become value stocks. Meta Platforms (META), Netflix, and Alphabet (GOOG) all currently appear in the Russell 1000 Value Index as well as the Russell 1000 Growth Index. In fact, Meta and Netflix have higher weights in the former than in the latter.

So, is GQG’s international offering still a growth fund? That depends whether one requires a growth fund to always sit in the growth portion of the style box or one accepts Jain’s broader definition. Will it stay in Morningstar’s foreign large-growth category? Category placement decisions for any fund depend on where its portfolio lands in the style box over several years, as well as what we expect it to look like in the future.

The Buzzer Hasn’t Sounded

As noted above, Jain’s willingness to move quickly, and the choices he made in doing so, have paid off. The emerging-markets fund would have fared much worse had he not jettisoned most of its Russian holdings quickly just weeks before they would have lost all value. And the international fund profited immensely in 2022 by turning away from tech toward energy and consumer staples.

That said, the emerging-markets fund’s 2022 return merely matched the dismal category average. And the international fund’s outperformance was limited to the first three quarters of the year. From Jan. 1 through Sept. 30, 2022, its 21.8% loss, though painful for shareholders, was much better than the 34.6% pummeling taken by the average foreign large-growth fund. It even outdid the foreign large-value average.

But in late 2022 market winds shifted, and the international fund felt the chill. From Oct. 1, 2022, through March 31, 2023, its gain lagged both category averages and the MSCI EAFE Growth and MSCI EAFE Value indexes. The emerging-markets fund also lagged its category average by a wide margin over that stretch.

Should Other Managers Try This?

Making rapid changes to chase stock market trends may pay off for a while, but that success often proves hard to maintain. It’s difficult, if not impossible, to consistently determine in advance when such trends will change. Excessive trading also can entail fees that eat into returns, even in an era of low-cost trading.

Jain, however, says his decision to dump tech stocks in favor of energy owed not to stock market trends but to hard data he saw in company financial reports, combined with his best estimate of future economic conditions. For example, he thinks fossil fuel demand will be remain strong for many years regardless of renewable sources’ progress.

However, even when based on accurate assessments of company fundamentals, it’s tough to succeed with a strategy of frequent, rapid portfolio shifts. For one thing, weak corporate results might reflect short-term events unrelated to a material change in their long-term prospects. In addition, different firms in the same sector can post divergent results; clear signals providing reliable guidance for an entire sector are uncommon.

Jain’s use of the term “regime change” is noteworthy. The implication is that moves such as his should occur only in response to major transformations that happen infrequently. Maybe that is the only way to successfully implement decisive shifts: with the caveat that you must be right and continue to be right for a decent period. The fact that Goldman Sachs GQG International Opportunities outperformed for most of 2022 provides only a brief vindication of that portfolio shift; it will take a longer period to determine whether it truly worked out.

The Limits

There’s another, more mundane reason most managers are unlikely to follow Jain’s lead. Formally or informally, their funds are designated as either growth, value, or core options, and advisors using them to build diversified portfolios for clients expect these funds to stay in their lanes. Suddenly moving from one side of the style box to the other won’t fly.

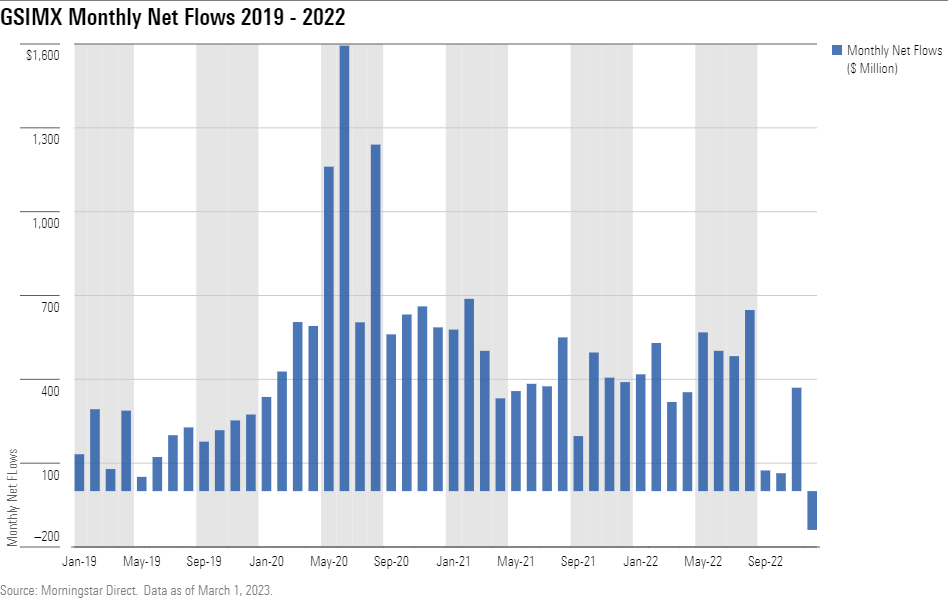

When asked by Morningstar whether he had received many complaints from shareholders about Jain’s shift, GQG’s CEO Tim Carver said no. Monthly figures show that the fund continued to receive net inflows throughout 2021 and the first 11 months of 2022, though the pace slowed significantly in 2022′s second half and changed to a small net outflow in December. (The net outflow could reflect shareholders responding adversely to the fund’s portfolio shift or could simply owe to investors engaging in tax-loss selling or reallocating assets at the end of a rough market year.

No doubt Jain’s long history of success has earned him the benefit of the doubt from many investors. That said, the fact that his moves resulted in a number-one rank in 2022 likely made the portfolio shift easier to accept. The story might be different if a similar shift doesn’t pay off; it wouldn’t be the first time a well-respected manager’s shareholders proved less loyal than expected when results flagged. Meanwhile, no matter how strong their reputation, most managers must answer to a chief investment officer and other overseers. Jain, as co-founder, CIO, and chair of GQG, does not. (Goldman Sachs acts as the distributor of the GQG international fund but has no say on its portfolio or investment decisions.)

What to Expect From Here

It’s unlikely, therefore, that we’ll see many other managers abruptly shifting from growth to value or vice versa, or taking a large-cap portfolio deep into small-cap territory. As for Jain himself, it’s not a given that he will repeat such actions anytime soon. He was responding to conditions as he saw them and will continue to do so, whether that means shaking up the portfolio or leaving it more or less intact for years. In other words, if the regime doesn’t change, neither will the portfolio. But if he considers it prudent to make another major move, he will do so.

In March Jain took another adventurous step. While not a portfolio transformation, it again demonstrated his willingness to buck conventional wisdom. When the share price of components of the Adani empire in India plunged after a critical report from a short-seller, Jain jumped in and invested in four companies from the conglomerate. Neither GQG nor Adani would say which funds invested or provide much detail beyond brief quotes. That said, the dollar figures cited in Adani’s news release made it clear Jain is not merely dabbling. It cited a total investment of $1.87 billion, which—given GQG’s overall asset base of $92 billion at the end of January—implies that these are likely meaningful but not excessive stakes for the funds involved.

Considering that the short-seller’s report engulfed Adani in controversy, Jain’s decision to buy four of its companies might surprise some people. But one aspect is no shock: Among the purchases was an energy firm.

Conclusion

Jain thus stands out in today’s mutual fund universe. Not only have his funds at Vontobel and GQG posted impressive records over lengthy periods of time, but he also displays a rare degree of flexibility in his investing style. In short, while the name “Goldman Sachs GQG International Opportunities” may lack the simplicity of “Magellan,” its manager feels no more limited by convention than did that distinguished investor of the pre-style-box era.