Warren Buffett's lessons about dividends

Dividends aren’t a magical source of returns, but they can offer an edge.

Mentioned: American Express Co (AXP), Brambles Ltd (BXB), Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA), Computershare Ltd (CPU), First Republic Bank (FRCB), Intel Corp (INTC), JPMorgan Chase & Co (JPM), Coca-Cola Co (KO), REA Group Ltd (REA), Starbucks Corp (SBUX), Snap Inc (SNAP)

Warren Buffett referred to dividends as the 'secret sauce' in his recent Berkshire Hathaway shareholder letter.

In the letter, he used two examples—Coca-Cola (KO) and American Express (AXP)—to make his case.

Berkshire purchased shares of Coke in 1994 for a total cost of $1.3 billion. The cash dividend Berkshire received from Coke in 1994 was $75 million. Last year, the Coke dividend paid to Berkshire was $704 million.

Buffett mentioned the following on Coke’s dividend growth: “Growth occurred every year, just as certain as birthdays. All [business partner Charlie Munger] and I were required to do was cash Coke’s quarterly dividend checks. We expect that those checks are highly likely to grow.”

In February, Coke raised its annual dividend for the 61st consecutive year.

American Express is a similar story. Berkshire’s purchases of American Express were completed in 1995 for the same dollar amount as Coke. Annual dividends paid to Berkshire have grown from $41 million in 1995 to $302 million last year.

Both Coke and American Express represent approximately 5% of Berkshire’s net worth today, roughly the same weight as when originally purchased.

Buffett went on to compare the performance of both investments against a 30-year bond. According to his calculations, the purchase of an investment-grade bond in the mid-1990s in place of Coke and American Express would now represent only 0.3% of Berkshire’s net worth and would be delivering “an unchanged $80 million or so of annual income.”

That’s significantly less than the $1 billion combined amount that Coke and American Express pay to Berkshire annually.

Importance of dividends in total return

Generally, increasing stock prices are the way most equity investors think money is made. But dividends play an important role as well.

Since 1993, the S&P 500 increased by 777% through the end of last year. With dividends included, the S&P 500 increased by more than 1,400% during the same period.

Dividends alone accounted for more than 20% of the S&P 500′s total return during this period, which is actually lower than past decades.

Dividends by decade

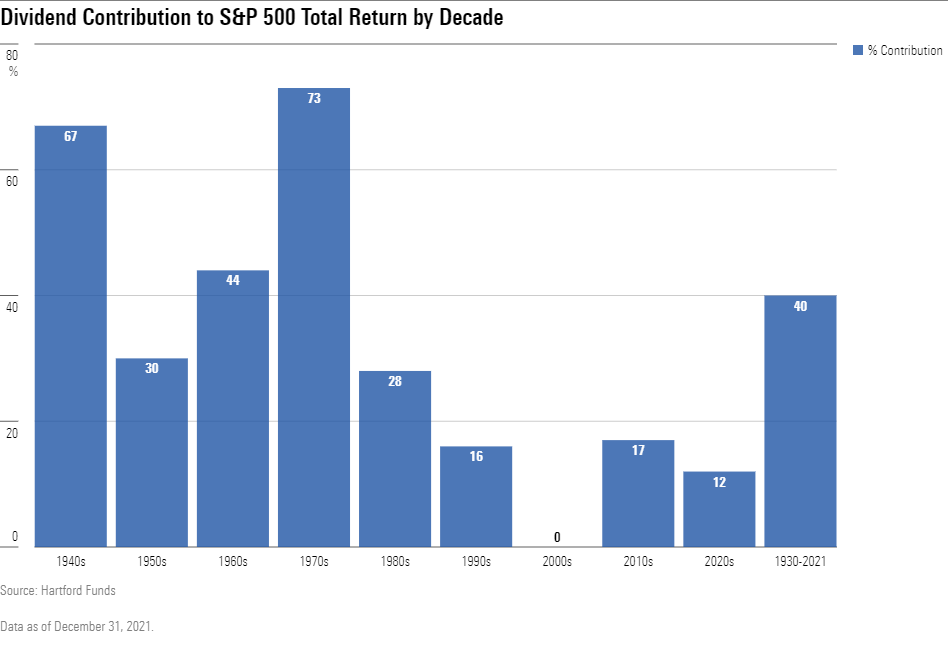

Looking at S&P 500 performance on a decade-by-decade basis shows how dividend contributions varied over time.

From 1930 to 2021, dividend income’s contribution to the total return of the S&P 500 averaged 40%.

Dividends can provide a huge tailwind on your long-term results if investors diligently reinvest them over the long haul.

Not all dividends are created equally

Investors seeking out dividend-payers may make the mistake of simply choosing companies that offer the highest yields. However, sometimes a high dividend indicates a dividend cut may be looming.

A recent example was Intel (INTC), which cut its dividend 66% in February. Intel’s founder Andy Grove wrote the seminal book Only Paranoid Survive in 1996. Over the past decade, Intel arguably lost its paranoid nature.

A plausible reason for the dividend cut was a result of excess cash being required for research and development to compete harder with companies that have taken market share.

When seeking out dividend-paying companies, it’s important to identify whether the dividend being paid will be consistent with opportunities to increase it over time, like Coke and American Express.

One way to do this is to evaluate companies based on economic moats. A castle with a physical moat is hard to penetrate. A business with a moat is equally hard to penetrate and more likely to keep competitors at bay.

Morningstar’s Dividend Select strategy has a strong preference for stocks with wide and narrow Morningstar Economic Moat Ratings, with 90% of the strategy’s assets invested in companies rated as having a moat.

Examples of moats

In a portfolio context, an advantage of having an economic moat is that it potentially makes it easier to manage through difficult periods. Even in a recession, companies with moats can face it with a stronger hand, given all the levers available.

Morningstar evaluates companies with moats across five key areas.

1. Switching Costs

Switching from one business to another can be a costly and timely process. When it would be too expensive or time-consuming to stop using a company’s products, that indicates pricing power.

For example, high switching costs are part of the reason ASX-listed share registry Computershare (CPU) was upgraded to a wide-moat rating this month. Analyst Shaun Ler says the cross-selling of services, like selling employee share plans and communication services together with issuer services, makes it time consuming and expensive for investors and businesses to switch providers.

2. Network Effects

A network effect occurs when the value of a company’s service increases for both new and existing users as more people use the service. For example, the more consumers who use American Express credit cards, the more attractive that payment network becomes for merchants. This in turn makes it more attractive for consumers, and so on.

Wide-moat REA Group (REA) has established network effects in its Australian residential real estate listings platform by creating and popularising the first digital listings platform for real estate in Australia.

3. Intangible Assets

Patents, brands, regulatory licenses, and other intangible assets can prevent competitors from duplicating a company’s products, or they can allow the company to charge higher prices.

For example, US-listed Starbucks (SBUX) is a business with an iconic brand. Last year alone, Starbucks raised menu prices three times with no obvious slowdown in traffic. Its brand and connection with consumers are one reason it was able to do so.

4. Efficient Scale

When a niche market is effectively served by one or only a handful of companies, efficient scale may be present.

For example, ASX-listed Brambles (BXB) is the only scale provider of pallet-pooling services operating globally. Its operating scale allows better customer service, availability and convenience for customers, underpinning its wide moat.

5. Cost Advantage

Firms with a structural cost advantage can undercut competitors on price while earning similar margins.

For example, cost advantage is an important source of the Big Four Banks' wide moat, which is also supported by a low-cost deposit base, operating efficiency, and conservative underwriting relative to peers.

Banking analyst Nathan Zaia says Commonwealth Bank’s (CBA) key funding cost advantage is the $800 billion or around 75% of funding which is sourced from customer deposits.

Judging a moat

While it may be relatively easy to identify a moat, it can be more challenging to accurately judge its size. It’s even more difficult to determine how long the moat will persist.

For example, a competitive advantage created by a hot new technology might not last.

The tech sector is littered with companies that go from playing “disrupter” to being “disrupted” in short order. Snapchat (SNAP) went from generating a massive amount of attention only to become an afterthought to TikTok in a few years.

When Morningstar evaluates a company’s moat, the first point of interest is historical financial execution. Firms that generate high rates of return on invested capital tend to have a moat, particularly if the returns are stable or increasing.

Yet the past tells us only what has happened, not what will happen in the future.

Morningstar attempts to determine how wide a moat is by asking, “Will the moat still be relevant in 10 or 20 years?”

Take JPMorgan Chase (JPM), for example, which benefits from multiple moats.

JPMorgan is the largest US money-center bank by assets and tends to have leading share and operations in almost all the areas where it competes. It has leading franchises in almost every banking product available. JPMorgan is particularly strong in investment banking, credit cards, asset management, and retail household reach.

It has switching costs (clients who bank with JPMorgan are unlikely to seek out financial services from other providers) and an incredibly strong brand.

This is a bank that not only survived the 2008 global financial crisis but saved other banks (Bear Sterns and Washington Mutual) that were insolvent during that period. With the recent demise of Silicon Valley Bank, JPMorgan showed its sturdy foundation providing capital to regional bank First Republic Bank (FRC).

JPMorgan’s brand has a reputation for weathering storms and being a provider of capital during hard times. And it’s likely its brand strength and relevance will help it retain current customers and attract new customers 10 and 20 years from now.

The importance of dividends

Dividends have historically played a significant role in total return.

When optimising for dividends, it’s important to consider whether the dividend is durable. One way to do this is to evaluate companies based on moats.

Many moats can be easily identified; however, figuring out their width and depth requires a deeper look. Moats can take years to build, but if the company does not have the necessary resources in place to maintain and grow it, that moat could quickly become a thing of the past.

“Morningstar is constantly evaluating and attempting to determine the strength and depth of company moats for inclusion in their dividend portfolio” says George Metrou, portfolio manager of the Dividend Portfolio separately managed account at Morningstar Investment Management.

Dividends are by no means a magical source of returns, but they do provide an edge (or slight advantage) in a portfolio.

By extension, slight edges can compound over many decades and end up feeling like magic.